Delta Air Lines: Fleet Simplification Will Be A Game Changer (NYSE:DAL)

As Winston Churchill famously said three-quarters of a century ago, “Never let a good crisis go to waste.” A crisis is exactly what Delta Air Lines (NYSE:DAL) and its airline industry peers are facing right now, as the COVID-19 pandemic has crushed air travel demand.

Yet, Delta, more than any of its peers, is taking advantage of this crisis to double down on existing strategies to improve its financial performance. Most significantly, it is accelerating a massive fleet simplification initiative first announced at its investor day last December.

Let’s take a look at the fleet simplification moves being carried out in 2020, Delta’s likely plans for the rest of the decade, the costs of its aircraft replacements, and the potential benefits for shareholders.

Mục lục bài viết

Major inefficiencies in the fleet

In Delta’s investor presentation last December, management drew a distinction between the current “legacy” fleet and the “optimal” fleet they were pursuing.

There are two main reasons why Delta Air Lines has been operating with a suboptimal fleet in recent years. First, Delta essentially doubled in size when it merged with Northwest in 2008. Some subfleets that were only operated by one of the two airlines are too small to be efficient for a carrier of Delta’s size. Second, in the years after the Great Recession, Delta was something of an aircraft value investor. In a quest to limit CapEx so that it could pay down debt, the airline accumulated unloved aircraft that could be bought or leased cheaply, adding further complexity to its fleet.

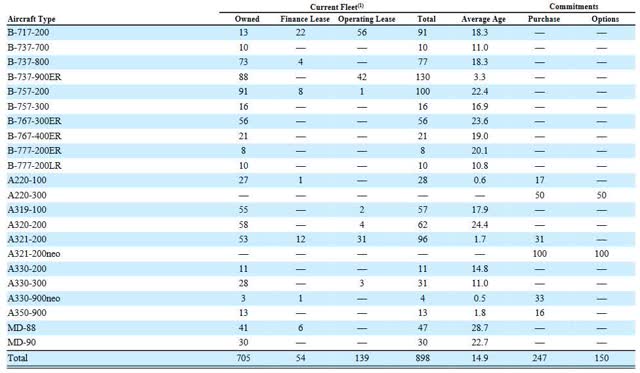

As a result, by the beginning of this year, Delta operated no fewer than 20 distinct mainline aircraft models, with two next-generation models set to join the fleet in 2020. Furthermore, some of those models have multiple configurations.

(Source: Delta Air Lines 2019 10-K SEC filing, p. 22)

Some level of fleet complexity is inherent in the network carrier business model, but there’s no reason Delta needs to operate 20 different aircraft models. Fleet simplification will reduce maintenance costs, boost pilot productivity, and provide greater flexibility to recover from operational disruptions. As a side benefit, the shift to a more modern fleet will also improve fuel efficiency.

Delta hasn’t wasted any time

It didn’t take long for Delta to start reshaping its fleet. Early in the pandemic, the carrier decided to retire all of its remaining MD-88s and MD-90s by June 2. The MD-88s would have exited the fleet by the end of 2020 anyway, while the MD-90s had previously been scheduled for retirement by 2022.

In May, Delta announced that it would also retire all of its Boeing (BA) 777s by the end of this year: both its eight 777-200ERs and its 10 777-200LRs. While the 777-200LRs are just 11 years old on average, operating such a small subfleet adds unnecessary complexity. The Airbus (OTCPK:EADSY) A350-900s that will replace the 777s are similar in size and burn 21% less fuel per seat.

Just last week, Delta announced that it will also retire its 737-700 fleet by year-end. While these planes are just 11 years old on average, there were only 10 of them in the fleet entering 2020 and they have particularly high unit costs.

With these moves, Delta will eliminate five of the 20 aircraft models in its fleet by year-end (although, as noted earlier, two new models will join the fleet soon: the Airbus A220-300 and A321neo).

Additionally, Delta is retiring some of its A320s and 767-300ERs. Both of these fleets average nearly 25 years of age and include aircraft that are nearly 30 years old. Between retiring its 77 MD-88/MD-90 aircraft and beginning its other fleet restructuring moves, Delta Air Lines reduced its mainline fleet from 898 aircraft to 804 aircraft during the first half of 2020.

What’s in the pipeline?

Even after the expected 2020 fleet changes, Delta will still have quite a lot of planes nearing retirement age. It will also have substantial incremental room to simplify its fleet.

First, Delta will retire its nearly 200 Boeing 757s and 767s by the end of this decade. The vast majority of these planes were built in the 1990s, although some were built as late as 2004. The 767s, in particular, play a vital role serving markets in Europe and South America and cannot be easily replaced. (Delta was hoping to be a launch customer for Boeing’s proposed NMA to serve this mission, but the NMA concept now appears to be dead.) As a result, many of Delta’s 767s and some of its 757s could remain in service past 2025. But given the age of these fleets, I would be shocked if any remain in service by 2030.

(Source: Delta Air Lines)

Second, the aging Airbus A320s (of which there are 52 following the recent retirements) will need to be fully retired. The majority of Delta’s A320s were built between 1990 and 1993 and are near the end of their useful lives. Even the newer ones were mostly built in the late 1990s, with a handful dating to as late as 2003. I expect all of them to exit the fleet within five years.

Third, as I have previously discussed, Delta may opt to retire its 91 Boeing 717s within the next two years, due to the need to refurbish them if they stay in the active fleet. Even if Delta does choose to extend the life of this fleet, the 717s (which are already nearly 19 years old, on average) would still be likely to retire by 2030.

The planes retiring in 2020 and the A320, 757, 767, and 717 fleets together account for 451 aircraft: roughly half of Delta’s mainline fleet entering 2020. Other aircraft models that could potentially be retired by the end of the 2020s include Delta’s 77 Boeing 737-800s, its 57 Airbus A319s, and its 11 A330-200s. The 737-800s and A319s were mainly built between 1998 and 2003, while the A330-200s date to the 2004-2006 period.

Some of these models may be phased out by 2030, but Delta has shown that it is able and willing to operate aircraft up to 30 years of age and even a little longer in some cases. The 737-800, A319, and A330-200 all share type ratings with other younger and larger models in Delta’s fleet, which should make it economical to keep these planes operating to an older age.

How much will it cost?

Depending on Delta’s growth rate and decisions around the 737-800, A319, and A330-200 fleets, the airline will likely need to acquire between 500 and 600 mainline aircraft over the next 10 years. Obviously, that will represent a significant capital outlay. However, it should be well within Delta’s financial capabilities.

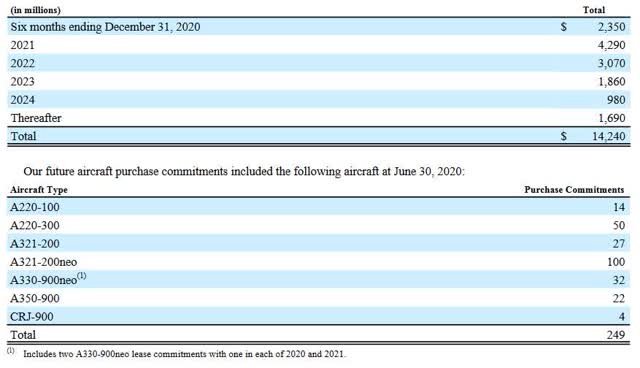

As of June 30, Delta had firm orders for 247 aircraft (excluding two lease commitments). These consist of four regional jets, 191 narrowbodies, and 52 widebodies. Estimated CapEx for these aircraft purchases totals $14.24 billion, most of which Delta is scheduled to spend between now and 2023, although the airline is negotiating order deferrals with Airbus.

(Source: Delta Air Lines Q2 2020 10-Q SEC filing, p. 23)

If Delta Air Lines ends up buying 500 aircraft over the next decade, total aircraft CapEx would likely be in the $28 billion-$30 billion range over the next decade. If it needed 600 aircraft, that figure could increase to a maximum of $35 billion. Averaged over 10 years, that would be little different than what Delta had initially planned to spend annually between 2020 and 2022.

Even that estimate may be too pessimistic. If Delta needs 250-350 aircraft within 10 years beyond what it has already ordered, it will have significant negotiating leverage with Airbus and Boeing, both of which will be desperate for new orders in the years ahead (especially Boeing). That could allow it to negotiate rock-bottom prices on new jets.

Additionally, while I expect Delta to mainly opt for new jets in the decade ahead, it could still supplement its fleet with cheap used aircraft in certain cases to reduce CapEx. One opportunity could be the expansion of its A330-200 fleet. There will likely be lots of mid-aged A330-200s on the market over the next few years, and this model may be the best Boeing 767 replacement available for the foreseeable future.

The benefits will be substantial

In late May, CFO Paul Jacobson said that the fleet retirements already in the works would save Delta “hundreds of millions of dollars” a year. There are a lot more potential savings where that’s coming from.

By the late 2020s, Delta is likely to have only 10-12 aircraft models from perhaps five distinct aircraft families, down from 20 models at the beginning of this year. This fleet transformation could also enable another significant increase in Delta’s average gauge (seats per aircraft), from around 127 at present to 150 or more by 2030.

(Source: Delta Air Lines 2019 Investor Day Presentation, slide 22)

This fleet simplification effort could cut the number of pilot aircraft categories at Delta in half. That should unlock efficiencies in pilot scheduling and reserve crew requirements, while also reducing the frequency of expensive training events. Adding in maintenance cost savings and gauge benefits, this fleet transformation could eventually generate double-digit unit cost savings: literally billions of dollars a year.

Fuel cost savings will also likely exceed $1 billion annually, depending on fuel prices. Most of the planes joining Delta’s fleet will be at least 20% more fuel efficient than those they replace.

It will take many years to unlock these savings, and a significant portion of the benefits won’t materialize until the 717, 757, and 767 fleets are fully retired. But for shareholders, the chance for Delta to finally deploy an optimized fleet is an opportunity worth waiting for.

If you enjoyed this article, please scroll up and click the follow button to receive updates on my latest research covering the airline, auto, retail, and real estate industries.