Propellerhead Software Reason

Virtual Music Studio

- Computer / Software

Industrious Swedish company Propellerhead are well known for their virtual instruments, but now they’ve made an entire software studio. Derek Johnson & Debbie Poyser bolt a few virtual devices into the virtual rack…

What would you say if £300 could buy you a complete electronic music studio, comprising a 14‑input automated digital mixer, 99‑note polyphonic ‘analogue’ synth, classic Roland‑style drum machine, sample‑playback unit, analogue‑style step sequencer, loop player, multitrack sequencer, eight effects processors, and over 500Mb of excellent synth patches and samples? OK — there’s a catch. This studio exists only in software.

The integrated software studio has been the coming thing for quite some time, but Propellerhead’s Reason, the bargain setup just described, is creating a buzz that only happens when a product has really tapped into the zeitgeist, and may just be the one that many of us have been waiting for. Propellerhead are not the first company to design a virtual studio — Creamware, for example, have already established their Scope and Pulsar systems — but the Swedes have given Reason a number of compelling hooks.

First, the Propellerhead name (of Rebirth RB338 ‘Techno Microcomposer’ and Recycle loop manipulator fame) brings a guarantee of quality and hipness. Secondly, Reason is cross‑platform, and requires no proprietary hardware. PCs need a suitable audio card, and a MIDI interface is necessary for both platforms, but unlike the Creamware systems, there are no dedicated DSP cards to buy. Thirdly, it uses an appealing and beautifully implemented ‘studio rack’ metaphor, which incorporates the vintage‑style elements clearly favoured by musicians. And let’s not forget that price!

In Reason’s self‑contained composition and sound‑designing system, synth sounds are created with a familiar ‘knobby’ analogue‑style synthesizer, samples manipulated with similar facilities to a hardware sampler’s, effects treatments applied, and tracks sequenced in two complementary ways. And contrary to what you might expect, it doesn’t necessarily demand massive computer power.

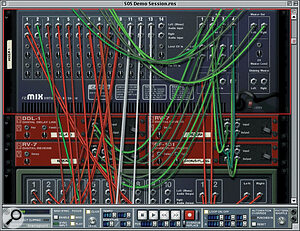

What Reason offers is not just every one of the components listed earlier, but as many of each as your computer can handle. They appear as graphic units in a rack, to which you can freely add or remove components. Signal routing between components usually occurs semi‑automatically, but flipping the on‑screen image reveals a back‑panel view of the virtual hardware, complete with animated pluggable cabling (not to mention electrical warnings and ‘manufacturing dates’, just like real hardware!). It gets busy back there, so Propellerhead have implemented colour‑coding: audio connections are in shades of red, effects cabling is green, and Gate and CV leads are yellow. (In case you’re questioning the need for Gate and CV connections in a software system, all but one of Reason’s devices use them for interfacing with the ‘analogue’ sequencer and other devices). The whole cabling idea is a fun aspect of Reason, and educational for novices, but cables can be hidden if preferred — in which case the various sockets retain a colour highlight.

Two on‑screen elements are always fixed to the rack: the Hardware Interface, which Propellerhead refer to as “riveted” in place, at the top, and the transport panel at the bottom. The Hardware Interface resembles a cross between a MIDI patchbay (the top section, featuring a bank of virtual LCDs showing Reason device MIDI channel assignments) and a meter bridge (the bottom part’s 64 bargraph meters showing audio output levels). At this point it’s worth mentioning that Reason doesn’t provide a two‑way street for MIDI and audio. You can’t record audio with it, or route external audio to Reason effects, and you can’t send MIDI data out. It’s meant to be a self‑contained system.

As the presence of 64 meters should suggest, the Interface provides up to 64 audio output channels, but if your soundcard is stereo, only two channels will be active. Likewise, up to 64 MIDI channels can come in, so that Reason’s virtual instruments can be played by sequencers other than the program’s two built‑in ones.

The transport panel has standard sequencer transport buttons, along with controls for setting tempo (up to 999.999bpm!), time signature (continually variable between 1/2 and 16/16), metronome click and locator points, plus a CPU load meter and an audio‑out clipping LED (which indicates output signal overload).

The next important component is the Remix mixer. Propellerhead advise starting new sessions by creating a Remix, to take advantage of their thoughtful automatic routing. Upon creation, the mixer’s output is automatically assigned to the Hardware Interface’s main stereo outs, and the outputs of any subsequently created sound‑producing devices are automatically plugged into a free mixer channel. The first four effects added are assigned to the mixer’s auxiliary send/return loops, too. These are a few of the many ways in which Propellerhead make life easier for Reason users. Mixer assignments can be changed later, of course, and devices may be plugged instead directly into the Hardware Interface if external mixing or treatment is envisaged.

Apparently graphically inspired by Mackie’s LM3204 line mixer, Remix is a deceptively simple device. It may look like a basic 14‑channel job, but its channels accommodate stereo inputs as easily as mono. Each input has a level fader, pan pot/balance control, four aux sends, two‑band EQ (24dB cut/boost at 80Hz and 12kHz — good, musical choices), mute and solo, level meter, and a graphic ‘scribble’ tape. The text on the last, usefully, echoes the name given to the sound source routed to the channel. Last up are a master fader and four aux return knobs.

When a session requires more than 14 inputs (the drum machine alone has 10 individual outputs!), multiple mixers are bussed together, summing master outs and aux sends. (Solo and mute controls only work for the Remix they appear on.) Remix parameters are controllable via MIDI or automatable via their own track in Reason’s main sequencer, and pan and level controls can be modulated from the analogue sequencer or other control sources.

Reason’s Subtractor synthesizer, so‑called because it’s based on a traditional subtractive architecture, is a very creditable software recreation of an analogue monosynth, except that it’s up to 99‑voice polyphonic! Of course, the more notes you play, the greater the CPU load.

Most of the features you’d expect from a genuine analogue synth are here, plus some you wouldn’t, or that are unique as far as we know. T he sound is spot‑on — Subtractor easily stood its ground next to a Korg MS2000R modelling instrument, as well as our genuine analogue synths (its sonic signature was closest to our Roland SH101, but it’s quite capable of emulating other synths). It comes with over 300 ‘presets’ but is, naturally, fully programmable.

Subtractor is equipped with two oscillators and a noise source, two resonant filters, amplitude, filter and modulation envelope generators, two LFOs, frequency modulation and ring modulation, and comprehensive gate and CV interfacing. Both oscillators offer 32 waveforms: analogue standards — sawtooth, square, triangle and sine — are augmented by 28 waveforms that behave more like samples or wavetables. They’re not ‘cheats’, exactly, but they do let you quickly achieve a certain character of sound without programming it from scratch. Each also has a nine‑octave range, plus coarse‑ and fine‑tuning controls. Disabling oscillator pitch tracking causes the oscillators to play a constant pitch, making the Subtractor ideal as a synth drum sound generator.

The synth’s innovative Phase Offset Modulation fakes an extra waveform derived from that being produced by an oscillator, offsets its phase, and allows that offset to be modulated. The main and offset waveforms can be multiplied or subtracted, producing further complex waveforms. POM creates oscillator sync‑like effects and something resembling pulse width modulation — the latter not restricted to square waves, as with PWM on ‘real’ analogue synthesizers.

The white noise generator, which can also produce the less bright sounds typical of red and pink noise, has an interesting decay control, independent of the amplitude EG. This could add flexibility when using noise to customise the attack of percussion or ‘wind’ sounds, giving the attack a decay separate from overall sound’s contour.

Subtractor’s dual filters are nicely specified and capable of treatments ranging from gentle to tweeter‑destroying. The main filter will probably manage most jobs, but the extra, simpler filter can add a further subtlety. Filter 1 has a variable characteristic (notch, 12dB/octave high‑pass or low‑pass, 24dB/octave low‑pass), plus frequency, resonance and keyboard‑tracking controls. Filter 2 is a fixed 12dB/octave low‑pass device with frequency and resonance controls.

No ‘analogue’ synth would be complete without Low Frequency Oscillators, to add movement to sounds by providing periodic modulation of selected parameters. Subtractor has two. The more sophisticated LFO 1 offers a choice of waveforms (triangle, sawtooth, inverted sawtooth, square, random and soft random), while LFO 2’s waveform is a fixed triangle. Both LFOs have rate and depth controls with a decent variety of modulation targets within the synth. In addition, LFO 2 has a delay control which fades its modulation in.

Pitch‑bend and mod wheels provide further real‑time control, both moving on screen in response to the wheels on a controller keyboard. The mod wheel is assignable in varying amounts, via knobs providing negative and positive values, to filter frequency and resonance, LFO1 depth, phase and FM. And there’s more: incoming aftertouch, breath controller or expression pedal data can modulate a range of parameters, too.

Creating a patch library is simple: edited patches can be saved at any time and appear in the pop‑up list in the synth’s virtual LCD. The many ‘presets’ are generally of high quality, if occasionally samey. You may also notice many having a digital edge: Subtractor is simple to program, and capable of analogue‑like warmth and fatness, but it’s all too easy to create sounds with an aliasing edge reminiscent of four‑operator Yamaha FM. On the other hand, this digital‑ness provides different sonic possibilities.

We can’t leave Subtractor without mentioning its ‘back panel’: CV and gate inputs, for triggering notes from the Matrix sequencer, are augmented by further modulation CV inputs, allowing eight Subtractor parameters to be modulated by CVs generated by the Matrix — or, as we shall see, other Reason devices. There are also three gate inputs, for independently triggering Subtractor’s EGs, and three CV outputs allow the synth’s mod EG, filter EG and/or LFO 1 to modulate compatible parameters on another Reason device. The mind boggles!

There’s wit in the NN19 sampler’s name — think Paul Hardcastle’s most memorable hit record! Actually, NN19 isn’t a sampler; it’s a sample player for AIFF‑ and WAV‑format samples. This fact represents a rare chink in Reason’s self‑contained armour, because to create and edit your own samples you’ll need sampling software, or a WAV‑compatible hardware sampler. ‘Editing’ in NN19 is limited to modifying a sample’s start time, tuning it and turning looping on or off.

Bar the lack of sampling and multitimbrality — and who needs the latter when you can create as many samplers as your computer can take? — NN19 is a great device. It handles multisamples with supreme ease, for example (though it lacks, sadly, velocity‑switched layers), automatically loading multiple samples and assigning them to keys on a MIDI keyboard display. Where appropriate, pitched samples are actually assigned to the correct key for their pitch! One nice multisample‑specific feature is ideal for piano samples, creating a realistic low‑ to high‑note spread between the left and right extremes of the stereo image.

A range of synth‑style parameters, including resonant filter and amplitude and filter EGs, is available for processing samples. Velocity response is customisable, and polyphony is up to 99 notes. Happily, CPU overhead is only consumed by notes played.

Gate and CV interfacing is virtually unheard of on hardware samplers — but NN19 has it. The sampler can be played monophonically from the Matrix sequencer using NN19’s CV and Gate inputs, and a handful of NN19 parameters may be modulated or triggered by CVs and Gates produced by other Reason devices. Lastly, NN19’s filter EG and LFO have CV outputs, enabling the sampler to be as integrated into Reason’s sound design and real‑time performance en vironment as Subtractor. The instrument sample patches provided in Reason’s free sound set are generally good — for dance loops see the next device!

Propellerhead’s first software was Recycle, jointly marketed with Steinberg. This novel loop‑manipulation tool (reviewed SOS May 1995) divides rhythmic samples into constituent beats and allows subsequent regrooving or retiming of the beats. Dr:rex (named after Recycle’s REX file extender) simply allows Recycled loops to be played back within Reason. Such loops can have their tempos changed in Dr:rex, via a special sequencer track, and their pitches changed without altering length. Synthesis options similar to NN19’s are also provided. There are no CV and gate inputs, as Dr:rex is triggered from the main sequencer, but other modulation ins and outs mean you can use loops almost as flexibly as any other sounds in Reason. Interestingly, Dr:r ex can handle the new stereo Recycle file format that isn’t due to appear in Recycle itself until version 2.0 is released (still a couple of weeks away at the time of writing).

You won’t be able to take full advantage of Dr:rex unless you own Recycle, but you could find inspiration in the varied collection of mono and stereo REX loops provided with Reason. Though mainly featuring contemporary drum loops, the collection also includes a range of instrumental riffs.

The hi‑tech market is awash with ancient drum‑machine recreations, undoubtedly because of the huge popularity of the sounds and pattern‑based programming interface of Roland’s TR808 and TR909. Propellerhead emulated both in v2 of their cult Rebirth RB338 software, and Redrum comes from the same mould. However, it doesn’t seek to copy the beatbox classics sonically, as any samples can be used as drum voices.

Redrum is a 10‑voice, pattern‑based drum machine featuring 32 patterns, each up to 64 steps long. (The 16 step pads for triggering drum hits are switchable in four banks.) Step resolution is variable between a half note and a 1/128th note — for those jungle snare blurs, no doubt — with triplet options; flam and three preset levels of ‘dynamic’ (accent) are available for each step. Usefully, the ‘dynamic’ setting is independent for every step of every voice’s part (some classics have a global accent value, and some accent all sounds on a given step). Patterns can be randomised or shifted a step in either direction, and are chained via a special track in the main sequencer.

Each voice has access to various modifying parameters, though not all voices have the same parameters. Velocity response, level, pan position and pitch parameters are common to all 10 voices, and they can all access two effects sends, but the remaining parameters differ depending on what type of sound a ‘slot’ is best suited to. No labels indicate which slots are intended for which voices, but the preset kits provide clues. You can put any sample into any slot, but some voice‑slot parameters suit cymbals, some toms, some snare, and so on.

Redrum offers a trigger out for each drum voice, so the pattern programmed for a voice could be played by, for example, a Subtractor synth drum patch. Trigger and pitch CV ins are provided for each voice, too. Incidentally, Redrum’s pattern programming system isn’t compulsory: drum parts may be programmed on a linear track in the main sequencer, using Redrum as a percussion ‘sound module’. In addition, pattern‑based drum tracks can be transformed into linear sequence tracks.

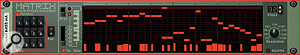

The inspiration for the Matrix single‑track step sequencer is obviously classic analogue step sequencers such as ARP’s 1600‑series and Doepfer’s modern MAQ16/3. The Matrix differs in that note values for its steps aren’t determined by a knob, as on a real‑world step sequencer, but by a grid. Simply click in the grid cell representing the note required on a given step (the display shows one octave of a switchable five‑octave range), and draw in a velocity value underneath it. You can tie neighbouring steps for held notes, and also, given the right sound, TB303‑like slide effects. Like Redrum, each Matrix offers 32 patterns, each with up to 32 steps and the same step‑resolution, randomise and step‑shift choices as Redrum. Patterns are chained in a special track in the main sequencer.

The Matrix also offers a secondary CV data track, with its own CV output, in addition to the main note‑generating gate and CV outs. This second CV output can modulate any controllable Reason device parameter. Thus a Matrix doesn’t necessarily have to produce notes, but may be set up just for modulation duties.

It’s hard to believe that something as simple as the Matrix could be such a creative tool. Yet working on music one note and one step at a time really focuses the mind on which notes are important. The resulting music is necessarily tightly quantised, but has unbeatable clarity — and for certain classic electronic music effects, nothing tops a step sequencer. Also, it’s possible to subvert the ‘rigid’ nature of step sequencing: setting up several Matrixes with different step lengths and resolutions, for adding pseudo‑random CV‑driven filter cutoff changes, say, to a repetitive synth part, can add as much interest to an arrangement as a studio full of multitimbral sound modules.

Through the magic of Rewire, Propellerhead’s internal audio and MIDI streaming technology that’s supported by many audio and MIDI software products, it’s possible to link their Rebirth software to Reason. Rewire syncs them together, and Reason’s Rebirth Input Machine brings all ReBirth’s audio outputs to the Reason mixer. Not surprisingly, this works very well. The transport of either application starts both, so you can work on Rebirth parts without continually returning to Reason.

On the subject of Rewire, Propellerhead have beefed up the protocol, which debuts as Rewire 2 in Reason. Rewire 2 improves MIDI and audio timing and increases the number of streaming channels between applications. So far Reason is alone in being Rewire2 compatible, but current Rewire‑savvy software should still be able to integrate with Reason.

![]()

Propellerhead have bolted eight neat processors, resembling Boss’s cute mid‑’80s Micro Rack series, into their virtual rack. They’re technically stereo in/stereo out, but are usable in mono (as insert effects), and all but one offer CV inputs.

- RV7 Digital Reverb: Though the RV7 won’t fool you into thinking a Lexicon PCM80 has invaded your computer, it does add the requisite feeling of space around Reason sounds. It’s perfect for synths, and doesn’t go boingy on drums (unless you want it to!). Basic algorithms include three halls, three rooms and gated reverb, with editable size, decay, high‑frequency damping and wet/dry balance. Software reverbs are known for hogging CPUs, but RV7 is moderate in its demands, yet still sounds pleasing.

- DDL1 Digital Delay Line: Provides up to two seconds of MIDI‑syncable delay, a choice of straight or triplet taps, feedback, pan and balance. Pan and feedback can be controlled by external CVs, to make the effect even more dynamic.

- D11 Foldback Distortion: Now this is something — a gritty or subtle sound destroyer. The distortion has a real digital edge to it, even at low levels, but it’s a killer process in the right context.

- ECF42 Envelope Controlled Filter: Just in case the filters on Subtractor, NN19 and Dr:rex aren’t enough, here’s another filter. Frequency, resonance, three characteristics (12dB/octave band‑pass or low‑pass, 24dB/octave LP) and EG are all provided for this eminently externally‑controllable device — frequency, decay and EG may be CV modulated, and EG triggered.

- CF101 Chorus/Flanger: A conventionally specified but versatile device with delay, feedback, LFO rate and amount parameters.

- P0 Phaser: A thoughtful design has provided a surprising amount of control over the ‘notches’ in the phasing process — under real‑time CV direction, too, if desired.

- COMP01 Compressor: Basic, but effective, and equally suitable for mix or instrument processing.

- PEQ2 two‑band Parametric EQ: Has a frequency range of 31Hz‑16kHz, with gain and Q controls. If only one band is required, disabling the second saves processor overhead. It sounds OK, if a little unsubtle, but the main problem is determining centre frequency: the device’s display isn’t specific, and the frequency parameter’s pop‑up value box (one of these pops up for every Reason parameter; Propellerhead call them Tool Tips) is only calibrated 0‑127.

Overall, the effects are simply but smartly implemented, and can easily be chained to create multi‑effects processing. Thus, anyone bemoaning the lack of pre‑delay and low‑frequency damping on the reverb can simply chain a DDL1, RV7 and PEQ2. Keeping track of such combinations (and their spaghetti‑like virtual wiring) is the worst aspect of this, but clear device labelling should keep you from getting lost.

All effects can be used in a Remix send/return loop, though not all are suitable. The D11, ECF42, COMP01 and PEQ2 are really insert effects, but the mixer lacks insert points. This problem is overcome by patching an effect (or several) in line with the sound being treated. Equally, to treat the Remix stereo out, simply patch the desired effect(s) between it and the Hardware Interface. The advantages are that Propellerhead didn’t have to design a potentially clumsy insert system for Remix, and that stereo signals can easily be treated.

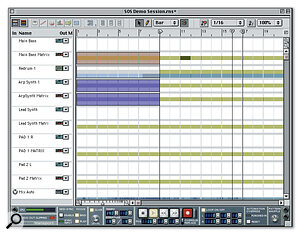

Reason’s main multitrack sequencer has much in common with standard track‑based MIDI sequencers, and many similar editing and manipulation tools, though there’s no score or event‑list editor, or tempo/time signature track. It’s possible to display all a sequencer’s individual tracks simultaneously in the Arrange view, or select a single track and see all its data, divided into lanes, in the Edit view. A full MIDI performance may be recorded, edited quite precisely with the clear piano roll‑type display, and tightened (or loosened) up with sundry quantising options, including groove quantise. Ten levels of Undo are available — as in the rest of the program.

There’s no sequencer track limit as such; Reason creates a track automatically for each sound‑making device added to the rack, but you can still create tracks for other devices, to allow them to be automated in the sequencer. Automation is recordable in real time — the sequencer records on‑screen control tweaks — or drawn manually in an automation lane editor. The automation lane editor gets crowded when you’ve created a large rack, but it remains one of the most elegant ways of handling automation that we’ve seen.

The main sequencer is also the central point for managing Matrix and Redrum pattern chaining, as previously noted. In addition, there’s a special grid‑format drum lane for editing or creating linear Redrum parts. A similar lane is available for creating or editing events that trigger individual beats within Dr:rex’s Recycle loops. Standard MIDI File import/export is supported, though the export option is a little eccentric: all channels behave as if they’re on MIDI channel 1, so even though the exported SMF is a multi‑channel Type 1 file, some sequencers may not untangle all the tracks during import.

Reason’s devices are admirable individually and work beautifully together, and it’s obvious how much thought, work and time has gone into making the program so streamlined and elegant. Propellerhead state in their very good Getting Started booklet: “At Propellerhead Software we are very much our own users. We make the products we want for ourselves.” This really shows in Reason.

Taking the devices individually, the Hardware Interface is a clear, comprehensible way of presenting MIDI in and audio out, and its 64 channels of each should more than suffice for most needs. The useful mixer works with the expectations of studio musicians, and its automatic device‑linking routines are really useful, especially for novices. Some way of grouping faders would be good, though.

Subtractor is one of the stars of the show. There’s little you’d be able to do with a hardware analogue that can’t be done with Subtractor, and it’s a bargain that such a well‑specified synth is included in such a low‑cost package. Programming is easy, fast and intuitive, and the sound is fantastic and very versatile. Phase Offset and the non‑traditional waveforms invite more modern‑s ounding synthesis, and the CV and gate options stretch sound design possibilities even further.

If the NN19 sample player could actually sample, it would be on a par with many hardware devices in terms of facilities, while the Dr:rex loop player works well and is invaluable for Recycle users — just as the Rebirth Input Machine will be welcomed by Rebirth devotees.

If you like Rebirth, you’ll love Redrum, which offers tons of fun for fans of classic drum machines and their old‑fashioned programming methods. The fact that synth sounds may be triggered instead of samples means that Redrum can become any kind of vintage drum machine: each voice in a genuine TR808 is a mini‑synth, for example, so the best way to replicate it is by using synths. It would be nice if the drum slots were labelled in some way to indicate which drum sounds they were intended for — even a clickable pop‑up label for each would be sufficient.

The Matrix is one of the more fiddly devices to use, both in terms of peering at the grid, and of trying to accurately position small note lozenges in the tiny grid spaces. Keeping track of what octave you’re working with can also be tricky. A small sideways keyboard graphic is supposed to help you figure out note pitches while moving lozenges, but a simple column of note names would be better. Alternatively, the keyboard keys could flash as the mouse reaches their pitch. Nevertheless, the Matrix is a favourite Reason device, a nostalgia trip back to writing with the likes of Roland’s MC202 Microcomposer. Its precision and suitability for creating monophonic lines should greatly appeal to dance and techno musicians — though its uses are certainly not confined to these styles. And for those times when a more conventional approach is preferred, the main linear sequencer is very usable and pretty powerful.

As for the effects, their minimal control sets makes them approachable and quick to tweak, and for more complexity they’re simple to chain. Gate and CV inputs allow certain effect parameters to be modulated in time with a song, and neat tricks like making an effect change in line with the contour of a synth patch, by connecting a synth’s envelope modulation output to an effect’s CV input, are achievable. It’s frustrating, though, that RV7’s effect cuts out when its ‘size’ parameter is altered.

Generally speaking, one niggle is that while Reason’s graphics are lovely, the text on screen is a bit small for comfort. Also, though Propellerhead have probably got it as good as it gets, operating software instruments via a computer keyboard, mouse and monitor is not always fun. Fortunately, MIDI hardware controllers can be easily integrated (see the ‘Control Zone’ box on page 204).

Latency, of course, is an issue for users of software instruments. When Reason noise makers are being played live over MIDI from a keyboard, there is some delay between pressing a key and hearing the sound. On our system it was fairly short — 34mS using an ASIO driver to patch Reason to our Digi 001 hardware. This is noticeable, but acceptable in many cases. Switching to the Mac Sound Manager driver reduced delay to 11mS. A Propellerhead spokesman notes that latency with MOTU audio hardware is just 3mS.

While we’re talking computer issues, let’s address CPU overhead. We found Reason very efficient. When we tried to make it fall over on our 450MHz G4 we reached 28 Subtractors, 28 Matrix sequencers, two mixers, a DDL1, an RV7, a P0 and a CF101, with all 28 Matrixes playing the same busy 16th‑note pattern at 120bpm. Reason’s CPU activity meter showed around 40 percent, and that was with other applications open. Adding another mixer, a Dr:rex, an NN19 with an eight‑way multisample, plus two fully‑loaded Redrums playing a medium‑busy pattern (as well as sequence tracks playing Dr:rex and NN19) caused CPU activity to hit 50 percent and the screen to begin struggling slightly. It was still possible to move faders and tweak knobs smoothly. One might expect that effects would consume more CPU overhead, but we got away with silly chains before the activity meter inched towards the red.

As for the wish list: we’d like an arpeggiator, and some way to provide multiple gate/CV outputs from one ‘lead’, so that one gate or CV could trigger or modulate multiple destinations. Some modular synth‑style processors for gates and CVs — such as lag processors — would be welcome. MIDI output would let Reason’s sequencers play hardware instruments and be MIDI sync master, and proper audio recording would really put the icing on the cake. The downside of the fact that Reason is a fully self‑contained system is that it’s not open to third‑party plug‑in or device development, and some people will undoubtedly wish they could use their favourite plug‑ins with it. (The plug‑ins of a Rewired application could, of course, be used, but not from within Reason itself.)

Propellerhead made an excellent start with Recycle and Rebirth, but Reason is bound to gain them a whole lot more fans and confirms their status in the big league of software developers. It would be impossible to be too positive about this package, which must be destined to sell in bucketloads, offering, as it does, such an amazing range of facilities, implemented in such a refined, userfriendly way, at less than the price of some single effect plug‑ins. Surely it shouldn’t be this cheap, easy, convenient and enjoyable to produce fantastic‑sounding tracks?

Mục lục bài viết

System Requirements

- MAC OS

Power Macintosh with 604/604e/G3/G4 processor, 166MHz or faster. (Reason is optimised for the G4’s Velocity Engine); 64Mb of RAM; CD‑ROM drive; Mac OS 8.6 or later; MIDI interface; MIDI keyboard; OMS 2.x (included).

- WINDOWS

Intel Pentium 2 or better, 233MHz or faster; 64Mb of RAM; CD‑ROM drive; Windows 98, NT 4.0 or 2000 (or later); 16‑bit Windows‑compatible audio card, preferably with ASIO or DirectX drivers; DirectX (if audio card supports it); MIDI interface; MIDI keyboard.

The review setup was a 450MHz Apple G4 (not dual processor) running Mac OS 9.0.4, with 384Mb of RAM (44Mb assigned to Reason), Digi 001 PCI card and 001 rackmount audio interface. Installation was easy and uneventful, including the necessary OMS setting up: Reason comes with an ASIO folder which houses the ASIO driver for your audio hardware. Mac users without audio hardware can choose the Sound Manager option in Reason’s Audio Preferences dialogue.

Automation

Reason allows nearly every control of every device to be automated. Simply create or select a track in the main sequencer for the device to be automated; go into record; wiggle knobs, press switches and tweak faders, as desired; stop; play it back. Any control that’s been automated is now highlighted on screen in green. Editing, or manually inserting, automation data, using a pencil tool in the main sequencer’s automation lane editor, is almost as easy as actually recording automation, but some way to automatically generate straight lines, for precise fades, for example, would be useful.

Saving Graces

When you save a Reason song, you save with it all the devices in the rack, selected patches (if any) for each device, device settings and offsets, Dr:rex loop assignments, Matrix and Redrum patterns, main sequencer tracks, rear‑panel cabling, and keyboard and MIDI controller assignments to devices. You can also save a device patch, as used by Subtractor and NN19. The patch saves all front‑panel settings, and references to samples in the case of NN19, but not rear‑panel cable routing or keyboard and controller assignments. There are no separate memories for Matrix and Redrum patterns or effects settings.

A Reason song, or section thereof, may also be saved as a stereo audio file in 16‑ or 24‑bit AIFF or WAV format, with a sample rate of between 11.025 and 96kHz.

Control Zone: Integrating MIDI Hardware Controllers

Assigning external MIDI controllers to Reason parameters is as straightforward as most other aspects of the program; the only problem will be supplying enough controllers for all the parameters you’ll want to tweak! In ‘learn’ mode, Reason pops up an empty window when an automatable parameter is clicked. Input the desired controller number into this, or simply move the MIDI control surface knob or fader you’d like assigned. The same goes for assigning the computer’s keyboard to control Reason switches, and even knobs.

Be aware that if you’ve, say, assigned all a control surface’s faders to Subtractor parameters and you move to working with another Subtractor, the faders still operate on the first Subtractor — controller assignments are per device. Most MIDI control surfaces have ‘patch’ memories, though, so it should be possible to create a patch for each Reason device and switch between patches on the control surface. The other thing to note is that controller assignments are saved with songs, not with Reason device patches; some way of copying controller assignments between like devices would be useful. Of course, you could create a template song with an average number of each device and your most‑used controller assignments, and use that as a starting point for new songs.

Super Shortcuts

A major problem with virtual instruments/studios is that parameters must be accessed via mouse and computer keyboard. Real‑time instrument control can be undertaken with MIDI fader boxes, but some basic software operations could still lead to RSI! Fortunately, Reason is well‑supplied with keyboard shortcuts and ‘context‑sensitive menus’. The manuals mention preset shortcuts (and you can customise more) but there’s no reference list, so here are a few Mac ones to get you started.

- Command/Apple‑2: expands linear sequencer window to full screen; Apple/Command‑1 hides it.

- Numeric keypad: controls transport. For example, Enter starts Reason, Zero stops playback (tapping twice returns to a song’s beginning) and ‘*’ enables record.

- Space bar: starts/stops playback, but without zero return.

- Arrow up/down keys: scroll through devices in rack.

- Document home/end keys: zoom to top or bottom of rack.

- Command/Apple‑click: resets selected knob to default value.

- Tab: toggles rear‑panel view.

- Command/Apple‑L: toggles hide/show cables.

- Each device has an arrow which shrinks it when clicked, to tidy up a busy rack ; Option‑clicking an arrow shrinks or enlarges all devices.

Context‑sensitive menus require use of the mouse, plus Control key, but since they cause menus to appear anywhere on screen, they save mousing up to the menu bar. The menu presented depends upon whether you Control‑click on a device or in a blank bit of rack: in the latter case, the menu includes a device list for easy device creation. Control‑clicking on a device displays copying and pasting options, plus device‑specific editing parameters.

Pros

- Superb value.

- Hugely usable and inspiring.

- Sounds great.

- Excellent choice of devices, with multiples of each available.

- Appealing and well‑designed interface.

Cons

- No audio recording/true sampling.

- No MIDI output.

- Screen legending small.

- System not open to third‑party plug‑ins and other devices.

Summary

Only a couple of months into 2001, and it looks like we’ve already discovered our favourite software of the year. Knockout.