The History of Money, From Fiat to Cryptocurrency

For decades, gold-pegged and fiat currencies formed the backbone of the global economy. But with bitcoin and altcoins, an alternative financial system is emerging, also known as decentralised finance. Here we explore humanity’s journey from using gold and paper money to cryptocurrency as legal tender.

Our in-depth articles are what they say: Here we go deep on topics that help you to develop fundamental knowledge of finances so that you can make confident choices. If you want to dive even deeper into the history of money, also check out part one of the history of money series, which explores the historical origins of money in barter and how the system evolved from trading cows for crops to sea shells and Chinese banknotes.

Mục lục bài viết

Overview

What is Commodity Money, Representative Money, and Fiat Money?

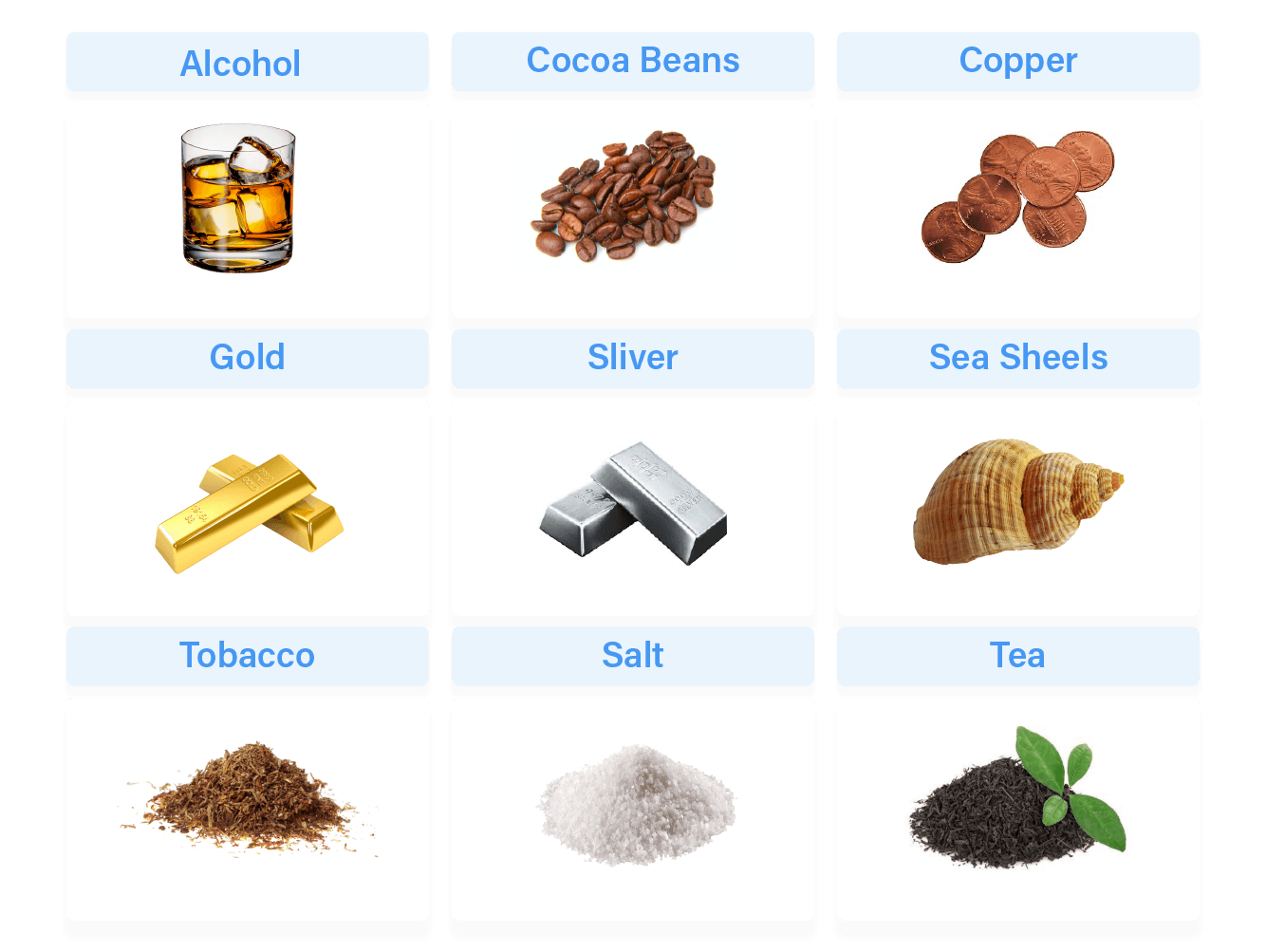

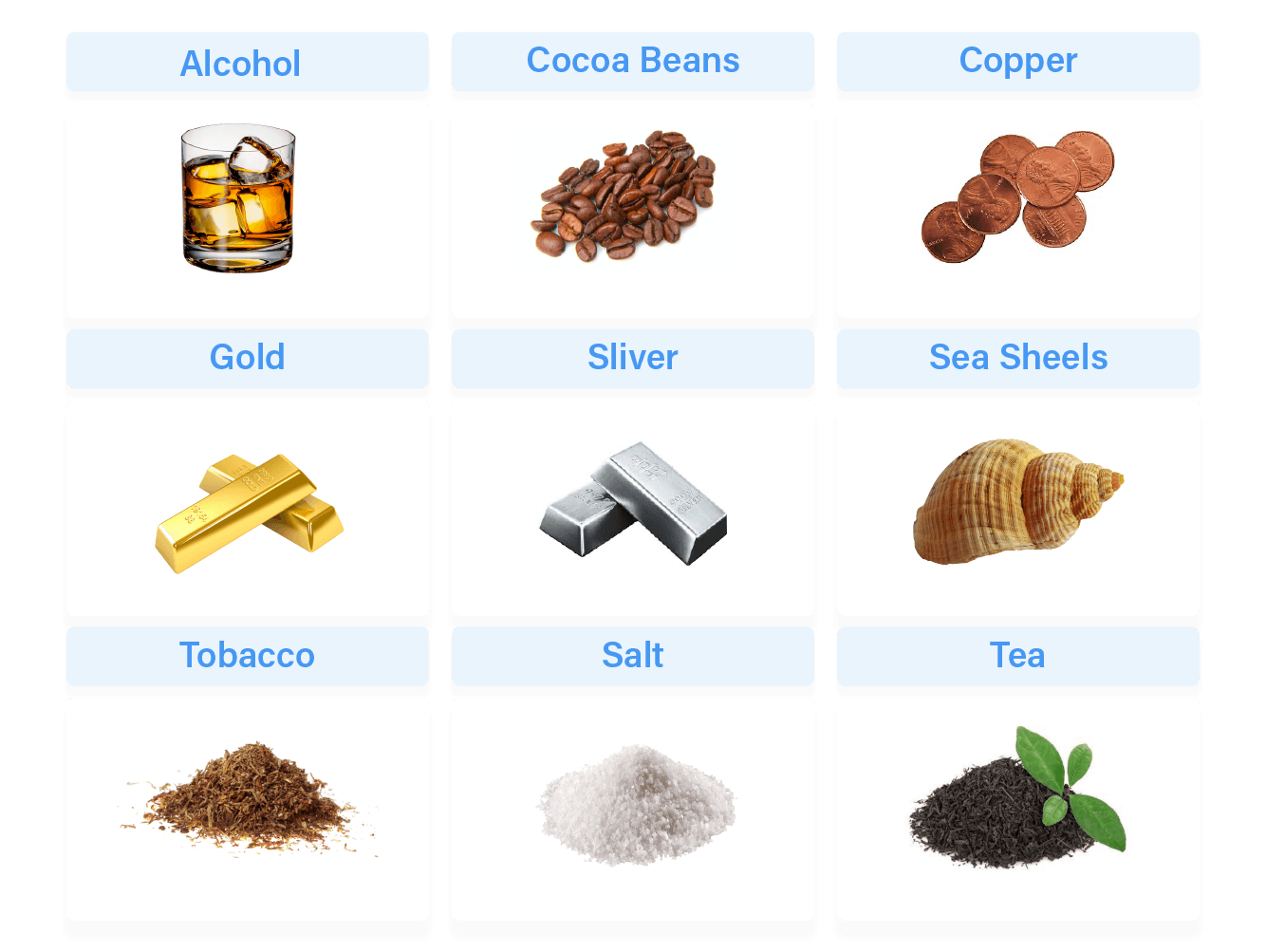

Commodity money is money whose value comes from a commodity of which it is made. Commodity money consists of objects having value or use in themselves (intrinsic value) as well as their value in buying goods.9

Examples of commodity money

Examples of commodity money

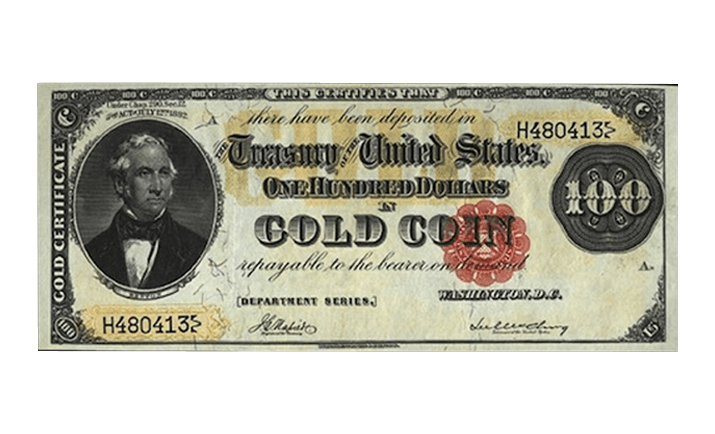

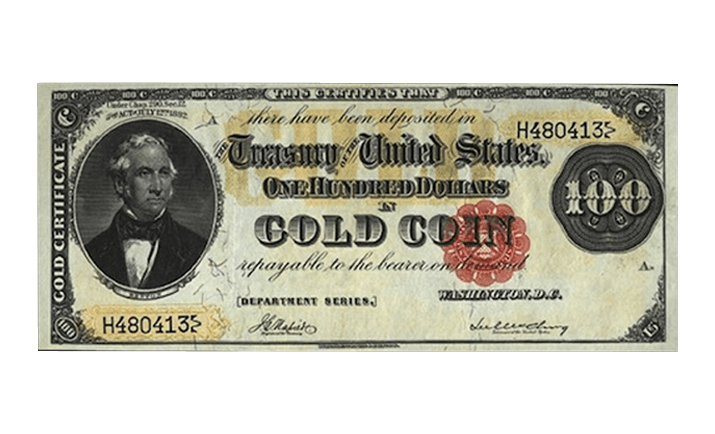

Representative money is any medium of exchange, often printed on paper, that represents something of value, but has little or no value of its own. Unlike some forms of fiat money, which may have no commodity backing, genuine representative money must have something of intrinsic value supporting the face value.10

The US dollar was backed by gold, which at that time made it representative money

The US dollar was backed by gold, which at that time made it representative money

Fiat money is a currency without intrinsic value that has been established as money, often by government regulation. Fiat money does not have use value. It has value only because a government maintains its value, or because parties engaging in exchange agree on its value.11

Examples of fiat money

Examples of fiat money

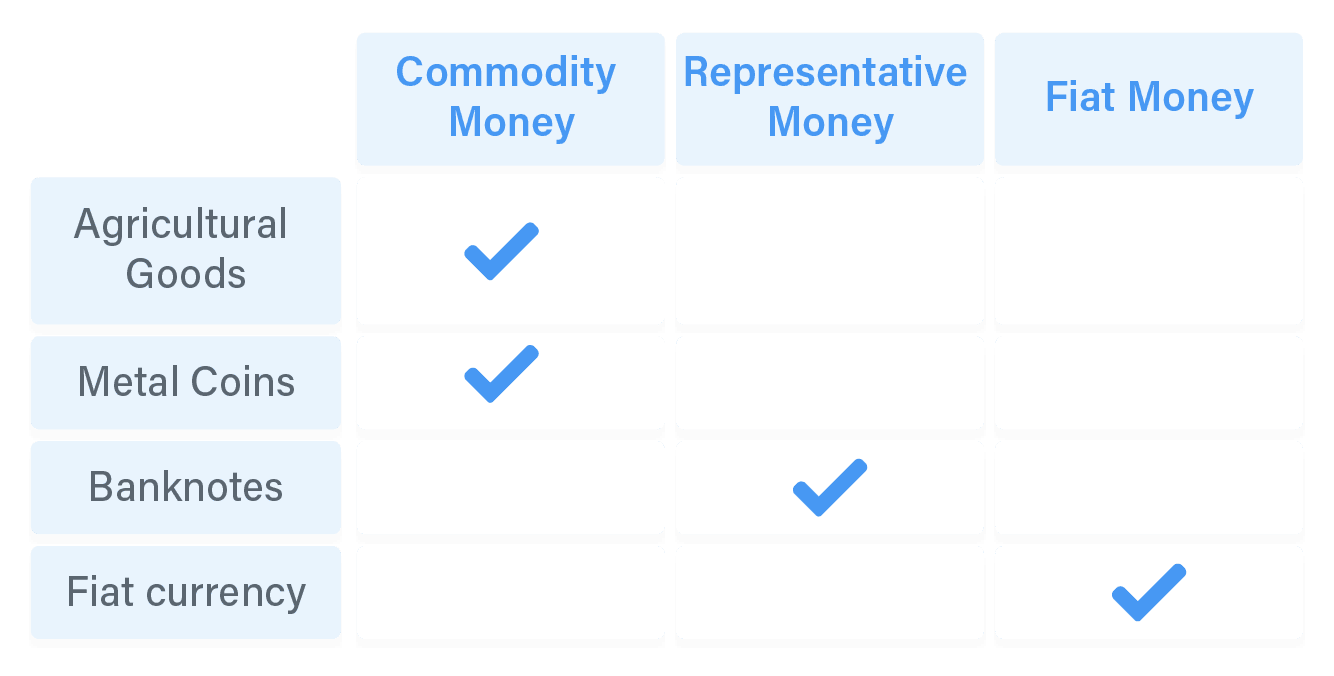

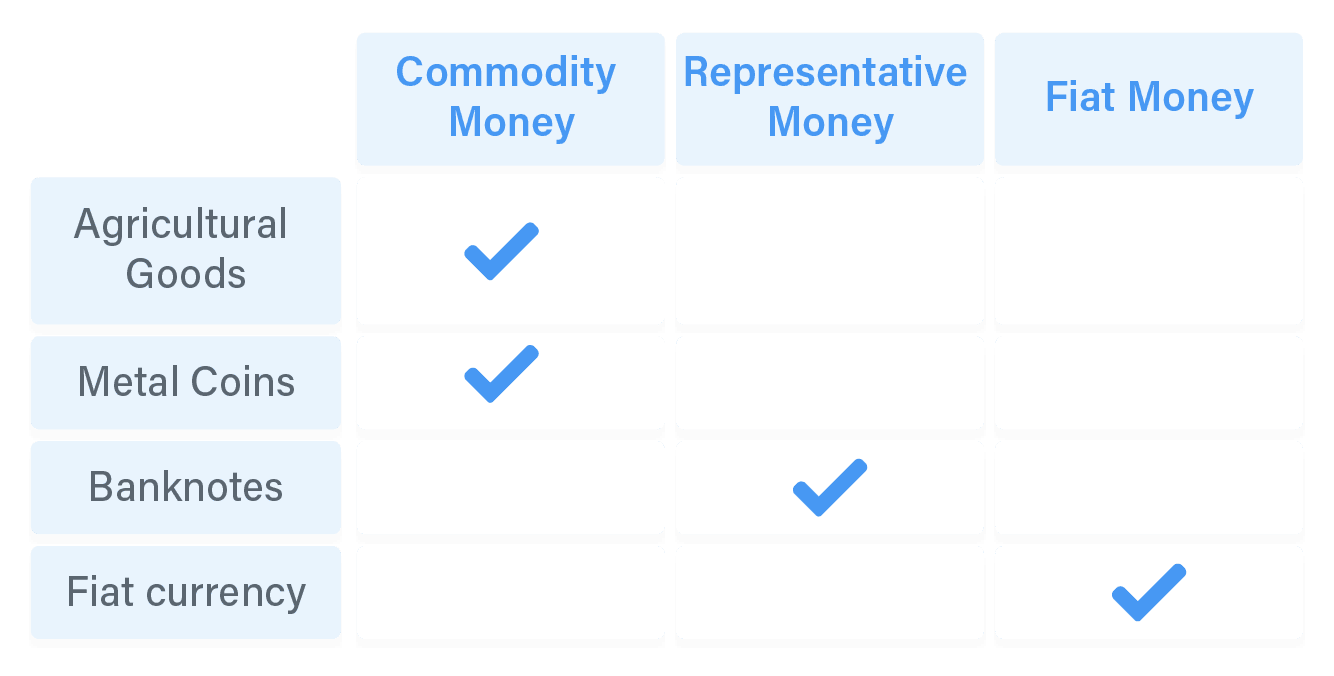

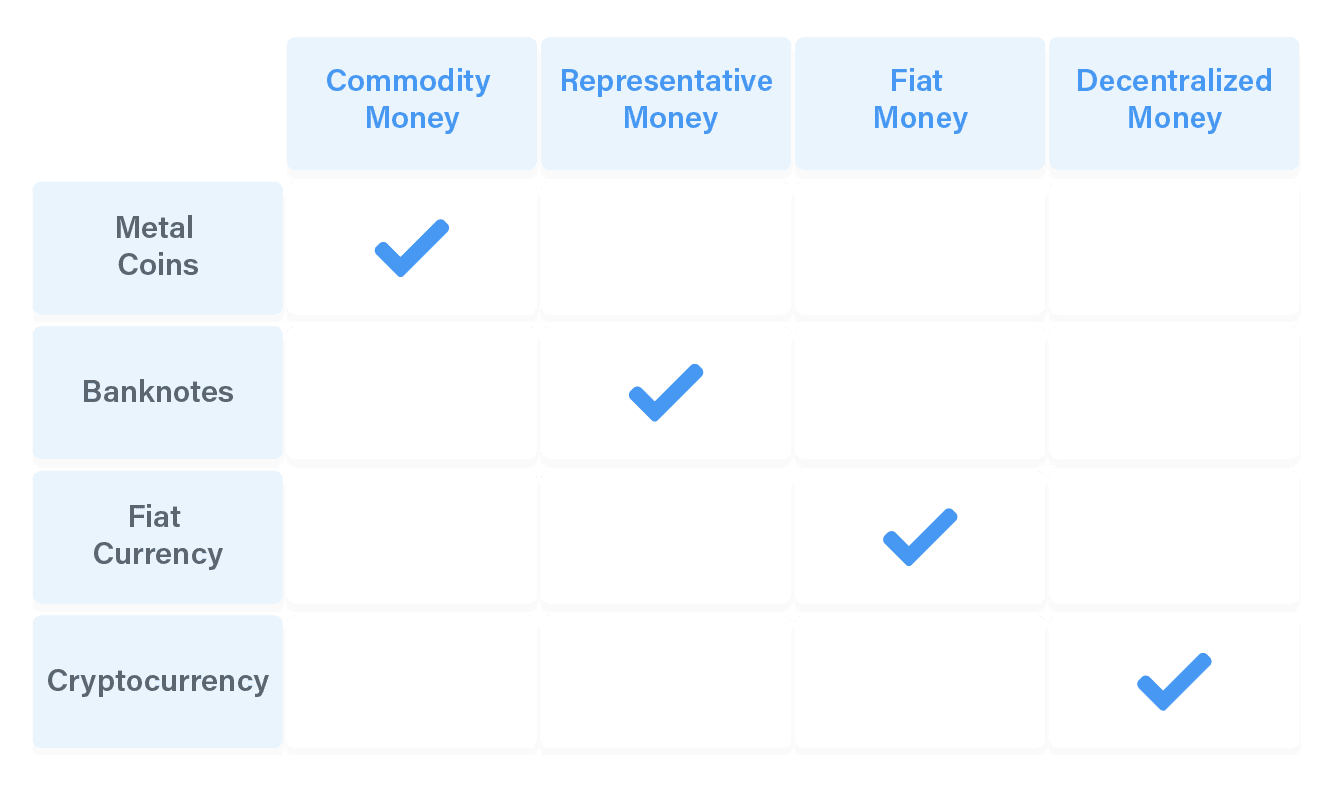

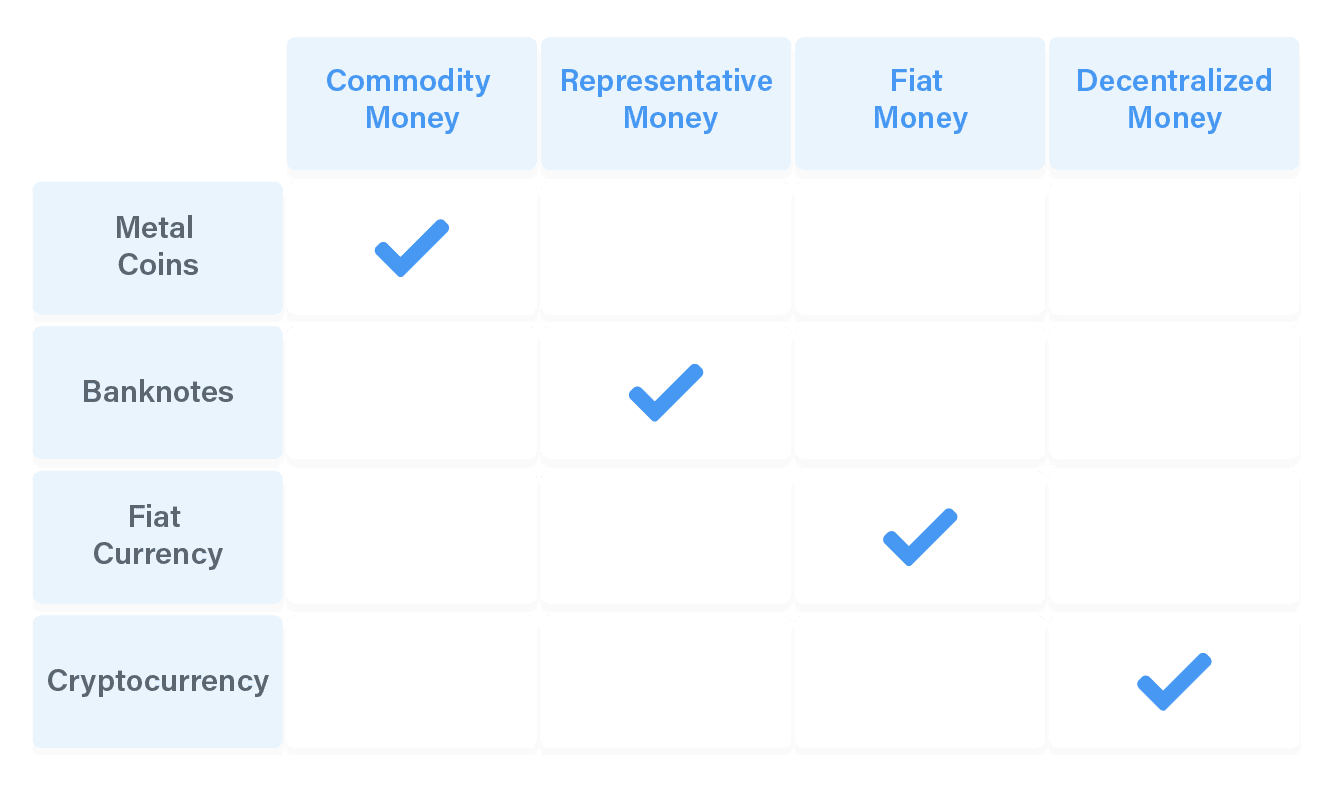

Here is an overview of different monies that have been used in history:

The Modern Art of Money

Money is gradually changing to a more abstract form. The earliest forms of money, like agricultural goods and seashells, were concrete, as they represent an immediate utility that can be consumed. In other words, they are consumption goods. This later changed to metal coins, where the underlying materials (i.e. metal) were capital goods (i.e., used in the production of equipment).

The introduction of banknotes marked the transition from commodity money to representative money, since it only represents a peg to metal coins, but in itself has no intrinsic value. After the abandonment of the gold standard, banknotes became fiat money, which is neither pegged nor possess intrinsic value.

The Gold Standard

As banknotes only represent a peg to its underlying metal coins, the intrinsic value of it is still determined by the demand and supply of its underlying metal. Some metals are too easy to be mined (e.g., copper), hence they are gradually losing their status as ideal money. This left only two candidates since they were hard to be mined, silver and gold.

The gold and silver standards are monetary systems in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold or silver.

The graph below summarises the intrinsic value of the gold and silver standards:

A volatile history: the gold standard’s rise and fall

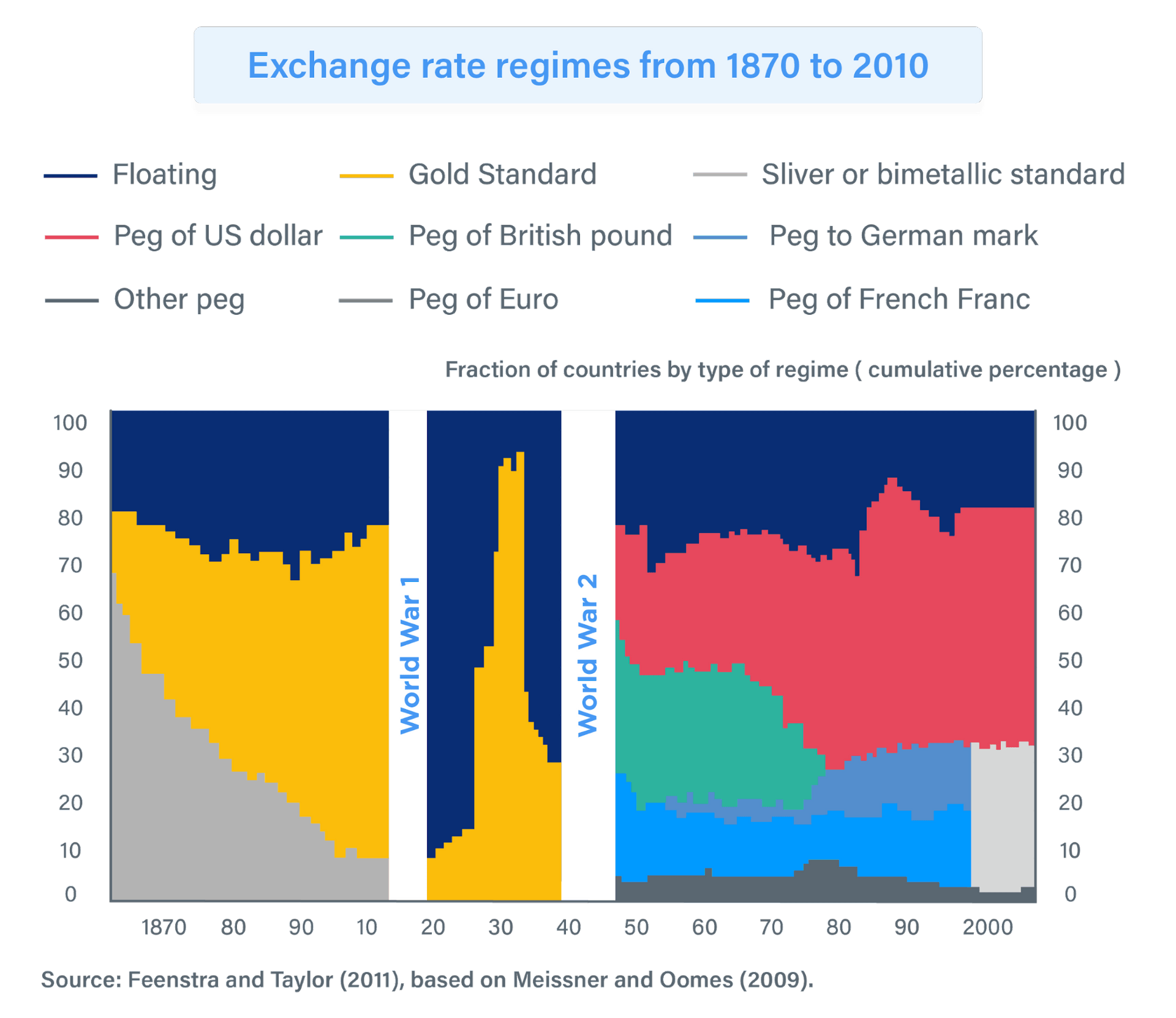

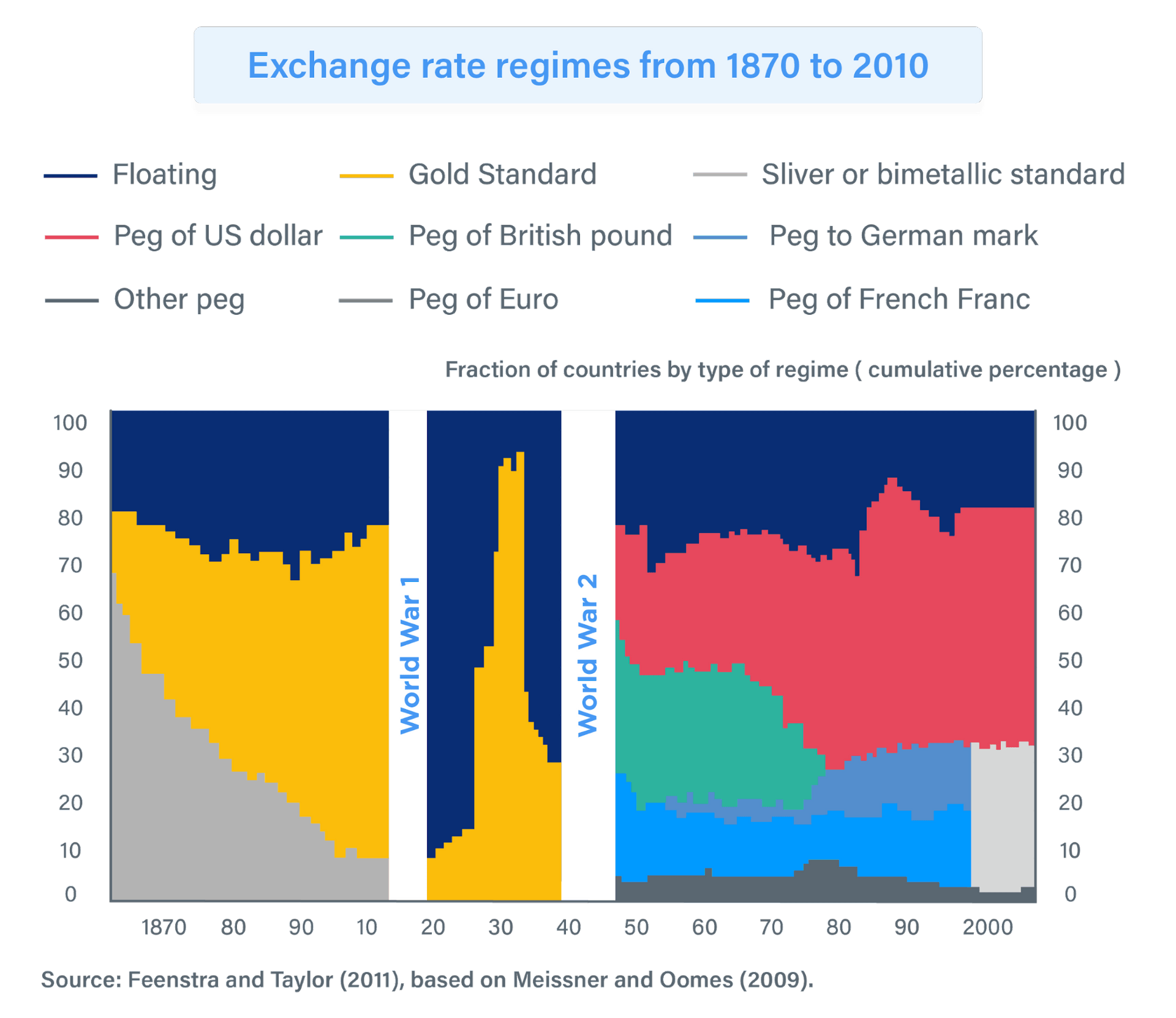

From 1870 to 1939, the history of international monetary arrangements was dominated by one story: the rise and fall of the gold standard regime.

In 1870 about 15% of countries were under the gold standard, rising to about 70% in 1913. This period was the first era of globalisation, with an increasingly large flow of trade, capital, and people between countries. A fixed exchange rate would be beneficial to facilitate the trades between countries, hence more and more countries were switching to use the same measurement standard.

One may wonder: why peg to gold? As we can see in the 1870s, most countries were still using the silver standard. One reason is the network effect – since the dominating country at that time, Great Britain, was using the gold standard, this led to all its colonies following. And if you utilised the gold standard, it lowered your trade costs with all British colonies. As more and more countries were adopting the gold standard, it created a snowball effect that brought all nations to a uniform standard.

However, not every country that joined the gold standard enjoyed it. The benefits were often less noticeable than the costs, particularly in times of deflation or in recessions. During World War I, countries participating in the war needed a way to finance themselves, and the gold standard forbade them to do so, since printing more money requires proportional ownership to gold. Hence, most countries began printing new money to finance the war afterwards, making their currencies free-floating from 1914 to the 1920s.

The Gold Standard Act of 1925

There was a return to the gold standard in the late 1920s to early 1930s as a result of The British Gold Standard Act of 1925. Many other countries followed Britain. However, the return of the gold standard led to a recession, unemployment, and deflation in these economies. This state of affairs lasted until the Great Depression (1929–1939) forced countries off the gold standard.

On September 19, 1931, speculative attacks on the pound forced Britain to abandon the gold standard. Loans from American and French Central Banks of £50,000,000 were insufficient and exhausted in a matter of weeks, due to large gold outflows across the Atlantic. The British benefited from this departure. They could now use monetary policy to stimulate the economy. Australia and New Zealand had already left the standard and Canada quickly followed suit.12

Countries that stuck with the gold standard (e.g. France and Switzerland) paid a heavy price: In comparison to 1929, countries that floated had 26% higher output in 1935, and countries that adopted capital controls had 21% higher output, as compared to countries that stayed on gold.13

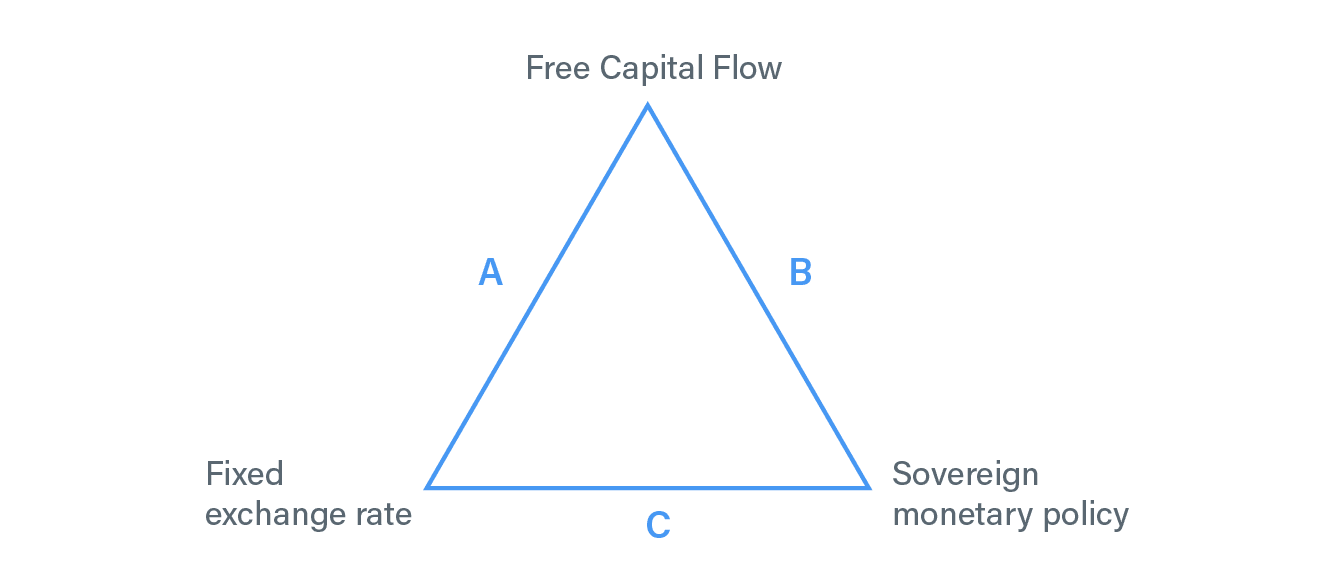

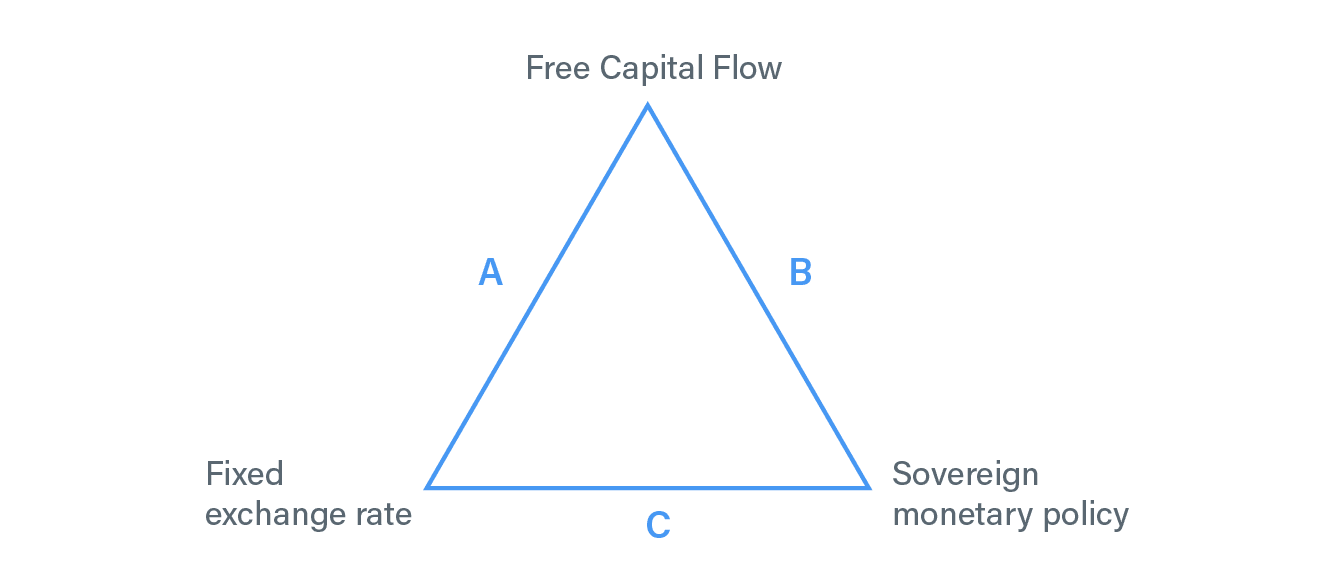

What a Trilemma: The Impossibility Trinity

The impossible trinity, also known as the trilemma, is a concept in international economics, which states that it is impossible to maintain all three of the following conditions at the same time:

- A fixed foreign exchange rate

- Free capital movement

- An independent monetary policy

It is both a hypothesis based on the uncovered interest rate parity condition and findings from empirical studies where governments that have tried to simultaneously pursue all three goals have failed. The concept was developed independently by both John Marcus Fleming in 1962 and Robert Alexander Mundell in different articles between 1960 and 1963.14

Picking sides

From 1870 to 1917, countries adopting the gold standard were picking side A, where they had a fixed exchange rate and free capital flow in order to facilitate international trade. After 1931, most countries abandoned the gold standard. They were either pegged to the US dollar (or British pound, French franc) (i.e. side A), following the Bretton Woods System (i.e. side C), or free-floating (i.e. side B).

It is possible to have some ‘middle ground’, such as ‘dirty floats’ or ‘pegs with limited flexibility.’ Hence monetary policies can be picked either at side A, B, or C, as well as some mixed choices in between.

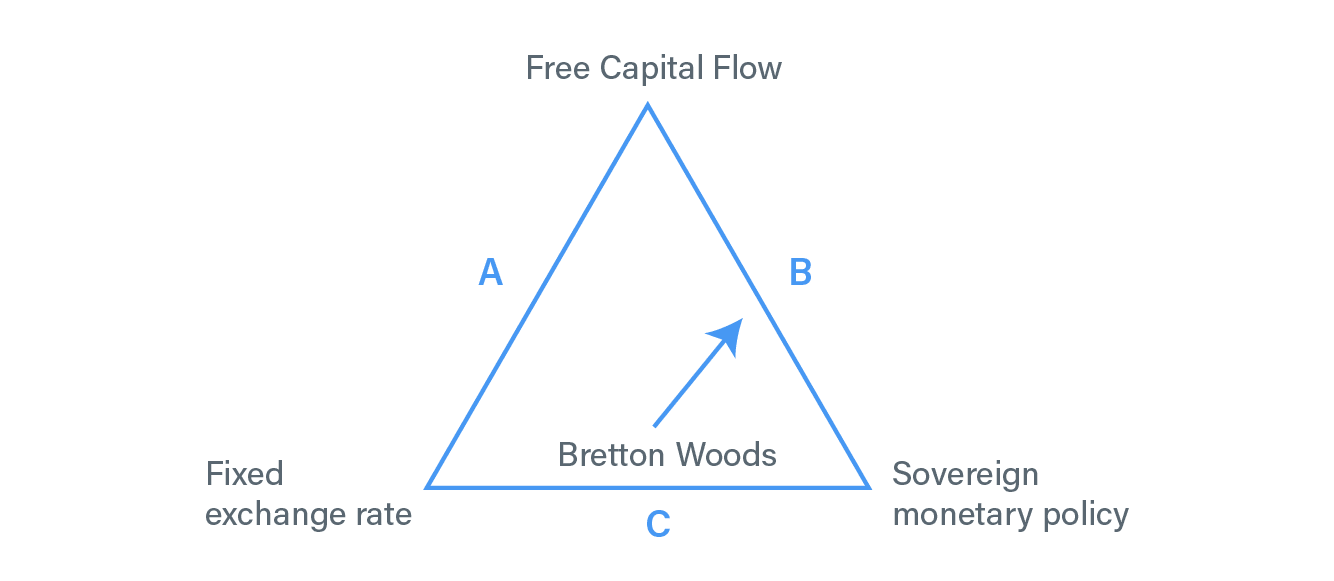

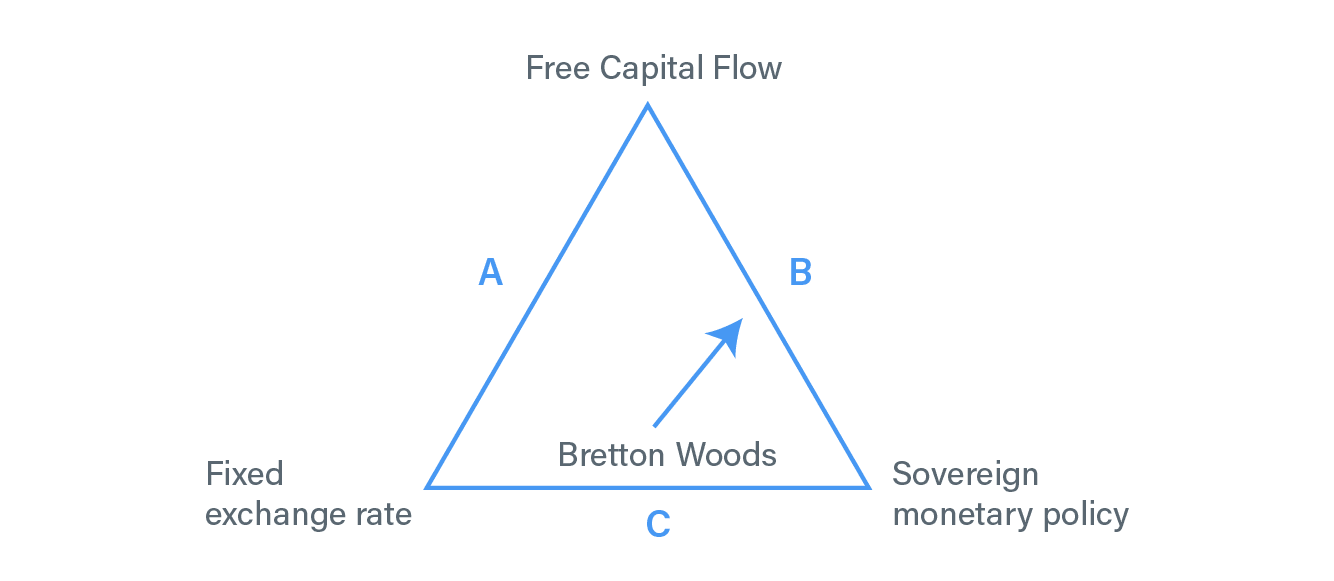

The Bretton Woods System

The international monetary system of the 1930s was chaotic. Near the end of World War II, allied economic policymakers gathered in the United States, at Bretton Woods, to try to ensure that the postwar economy fared better. The architects of the postwar order, notably Harry Dexter White and John Maynard Keynes, constructed a system that preserved one key tenet of the gold standard regime – by keeping fixed rates – but discarded the order by imposing capital control and therefore opting for side C.

The Trilemma was resolved in favour of exchange rate stability to encourage the rebuilding of trade in the postwar period. Countries would peg to the US dollar; this made the US dollar the centre currency and the United States the centre country. The US dollar was, in turn, pegged to gold at a fixed price, a last vestige of the gold standard.

However, imposing capital control is difficult. Controls in the 1960s already became leaky and investors found ways to circumvent them and move money offshore from local currency deposits into foreign currency deposits. Some even used accounting tricks to move money from one currency to another.

The end of the dollar peg

As capital mobility grew and controls failed to hold, the trilemma tells us that countries pegged to the dollar stood to lose their monetary policy autonomy. This was a reason for them to rethink their dollar peg. As it became more apparent that US policy was geared to US interests only, the commitment to convert dollars into gold no longer existed.

Some countries started to frequently devalue their currency or even cancel the peg to the US dollar.

The Bretton Woods System dissolved quietly. Since then, the international monetary system has transited into the era of fiat currency.

So, What is Fiat Currency Worth?

Fiat money is a currency without intrinsic value that has been established as money, often by government regulation. Fiat money does not have use value, It has value only because a government maintains its value, or because parties engaging in exchange agree on its value.15

Fiat money started to dominate in the 20th century. Since the decoupling of the US dollar from gold by Richard Nixon in 1971, a system of national fiat currencies has been used globally.

Fiat money has been defined variously as:

- Any money declared by a government to be legal tender

- State-issued money which is neither convertible by law to any other thing, nor fixed in value in terms of any objective standard

- Intrinsically valueless money used as money because of government decree.

- An intrinsically useless object that serves as a medium of exchange (also known as fiduciary money)

From the history we have discussed, we can see that fiat currency is not appearing suddenly but how we gradually transitioned into this system. Countries have tried to tie to the gold standard but eventually failed because governments need flexibility and tools to regulate the economy, and the cost of sovereignty insolvency may outweigh the drawbacks of letting the government control the money supply.

However, allowing the government to print new money creates another problem, inflation tax. Suppose you are holding one dollar, and one dollar can buy you an apple. If the government is printing out one more dollar, the total dollar supply in the market becomes two, and now you can only buy half an apple. Issuing new currency is considered a tax on holders of existing currency.

Shaking the Fiat: The Subprime Mortgage Crisis and Quantitative Easing

The United States subprime mortgage crisis was a nationwide financial crisis, occurring between 2007 and 2010, that vastly contributed to the U.S. recession of December 2007 – June 2009. It was triggered by a large decline in home prices after the collapse of a housing bubble, leading to mortgage delinquencies, foreclosures, and the devaluation of housing-related securities.16

The housing bubble preceding the crisis was financed with mortgage-backed securities (MBSes) and collateralised debt obligations (CDOs), which initially offered higher interest rates (i.e. better returns) than government securities, along with attractive risk ratings from rating agencies. While elements of the crisis first became more visible during 2007, several major financial institutions collapsed in September 2008, with significant disruption in the flow of credit to businesses and consumers and the onset of a severe global recession.

Quantitative easing as the silver bullet?

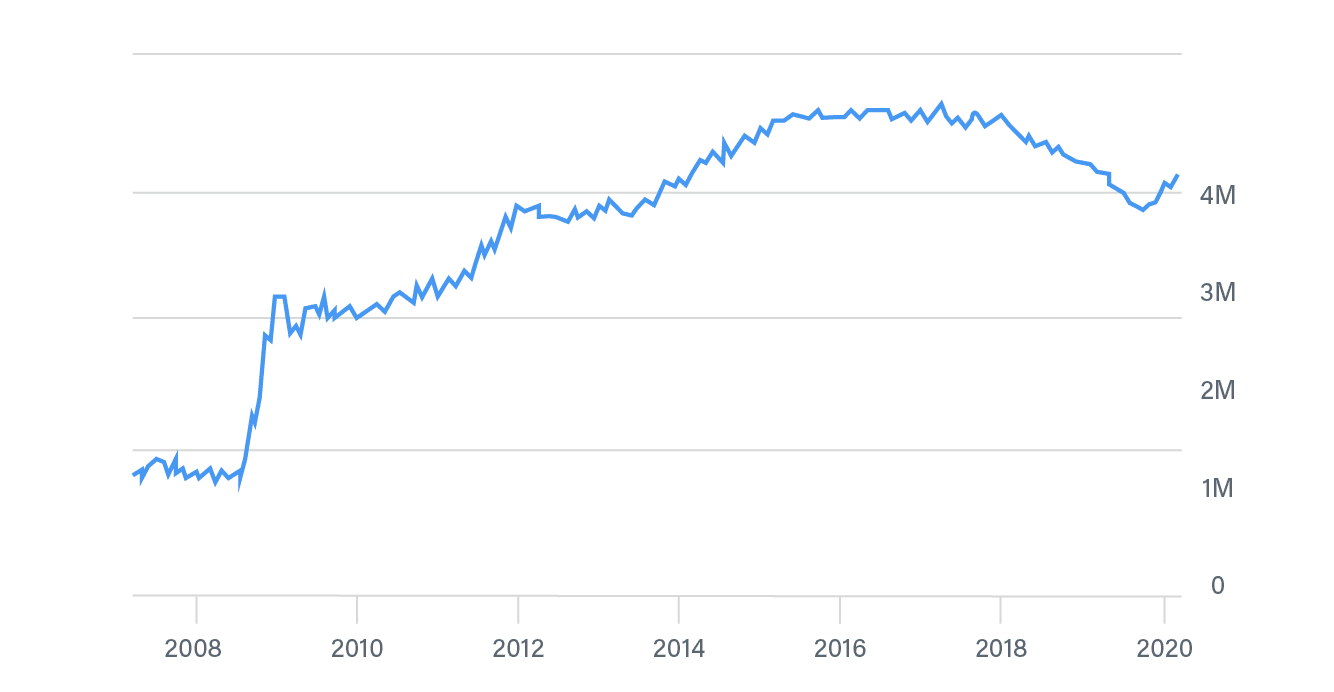

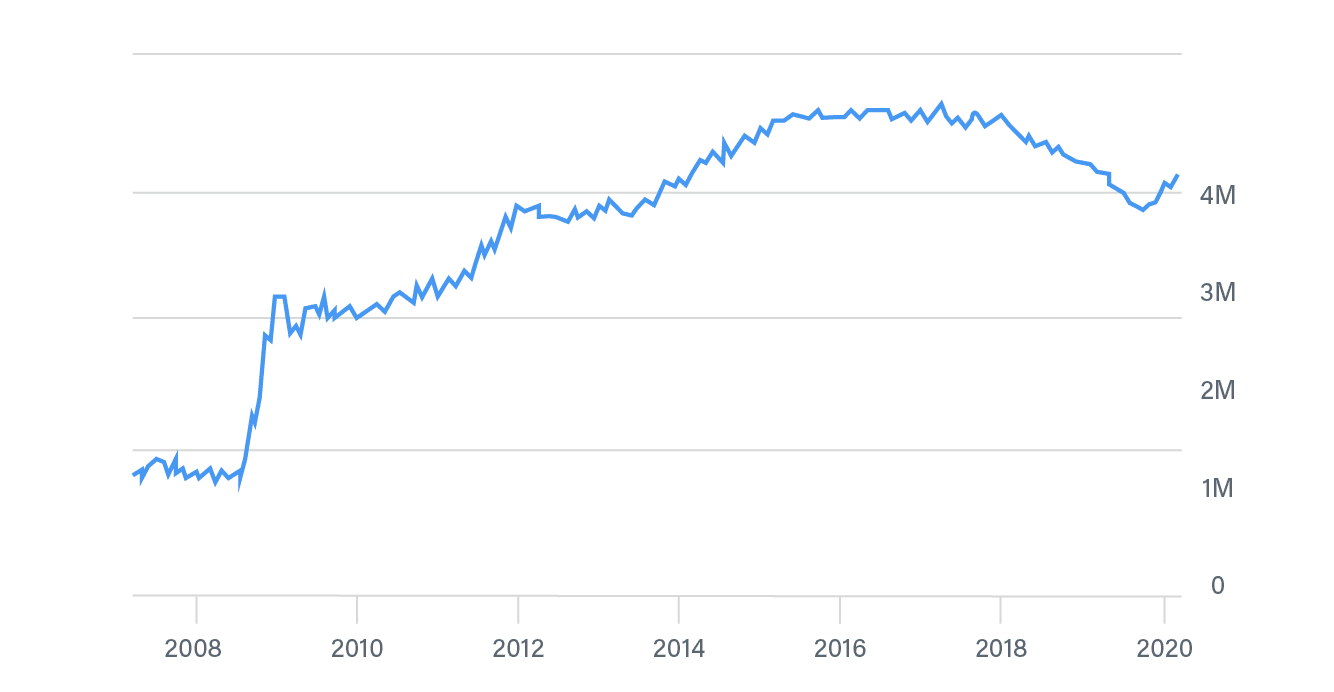

The US’s solution to the recession is Quantitative Easing (QE), which is a monetary policy whereby a central bank buys predetermined amounts of government bonds or other financial assets in order to inject liquidity directly into the economy. A central bank implements quantitative easing by buying specified amounts of financial assets from commercial banks and other financial institutions, thus raising the prices of those financial assets and lowering their yield, while simultaneously increasing the money supply.17

By March 2009, the Fed had repurchased 1 trillion of bank debt, mortgage-backed securities, and treasury notes, and all the cash used to repurchase these assets was flowing out to the market. This amount reached a peak at 1.35 trillion in June 2010.

In November 2010, the Fed announced a second round of quantitative easing, buying $600 billion of Treasury securities by the end of the second quarter of 2011. The market called it the “QE2”.

“QE3” was announced on 13 September 2012. The Federal Reserve decided to launch a new $40 billion per month, open-ended bond purchasing program of agency mortgage-backed securities.

We can see that the Fed Balance sheet is rapidly increasing after the QE started. The value before QE is USD 900 billion and reached USD 4 trillion today. The difference is all the liquidity (i.e. money supply) that has been injected into the economy until today.18

Growing Fed reserves under quantitative easing

Growing Fed reserves under quantitative easing

Quantitative easing has led to many problems, one notable issue is income and wealth inequality. British Prime Minister Theresa May openly criticized QE in July 2016 for its regressive effects:

“Monetary policy – in the form of super-low interest rates and quantitative easing – has helped those on the property ladder at the expense of those who can’t afford to own their own home.19” In 2012, a Bank of England report showed that its quantitative easing policies had benefited mainly the wealthy and that 40% of those gains went to the richest 5% of British households.

Finally: The Arrival of Bitcoin

Finally here comes bitcoin. Satoshi Nakamoto created Bitcoin in 2008 and also voted against the trust towards central bank-owned currencies:

“The root problem with conventional currency is all the trust that’s required to make it work. The central bank must be trusted not to debase the currency, but the history of fiat currencies is full of breaches of that trust. Banks must be trusted to hold our money and transfer it electronically, but they lend it out in waves of credit bubbles with barely a fraction in reserve. We have to trust them with our privacy, trust them not to let identity thieves drain our accounts.20“

Satoshi Nakamoto

It should be noted that bitcoin is not the first attempt at digital currency. Before bitcoin, there were DigiCash (founded in 1989 by Cryptographer David Chaum) and E-gold (founded in 1996 by oncologist Douglas Jackson and lawyer Barry Downey). However, both projects failed due to centralisation.

Is bitcoin ideal money?

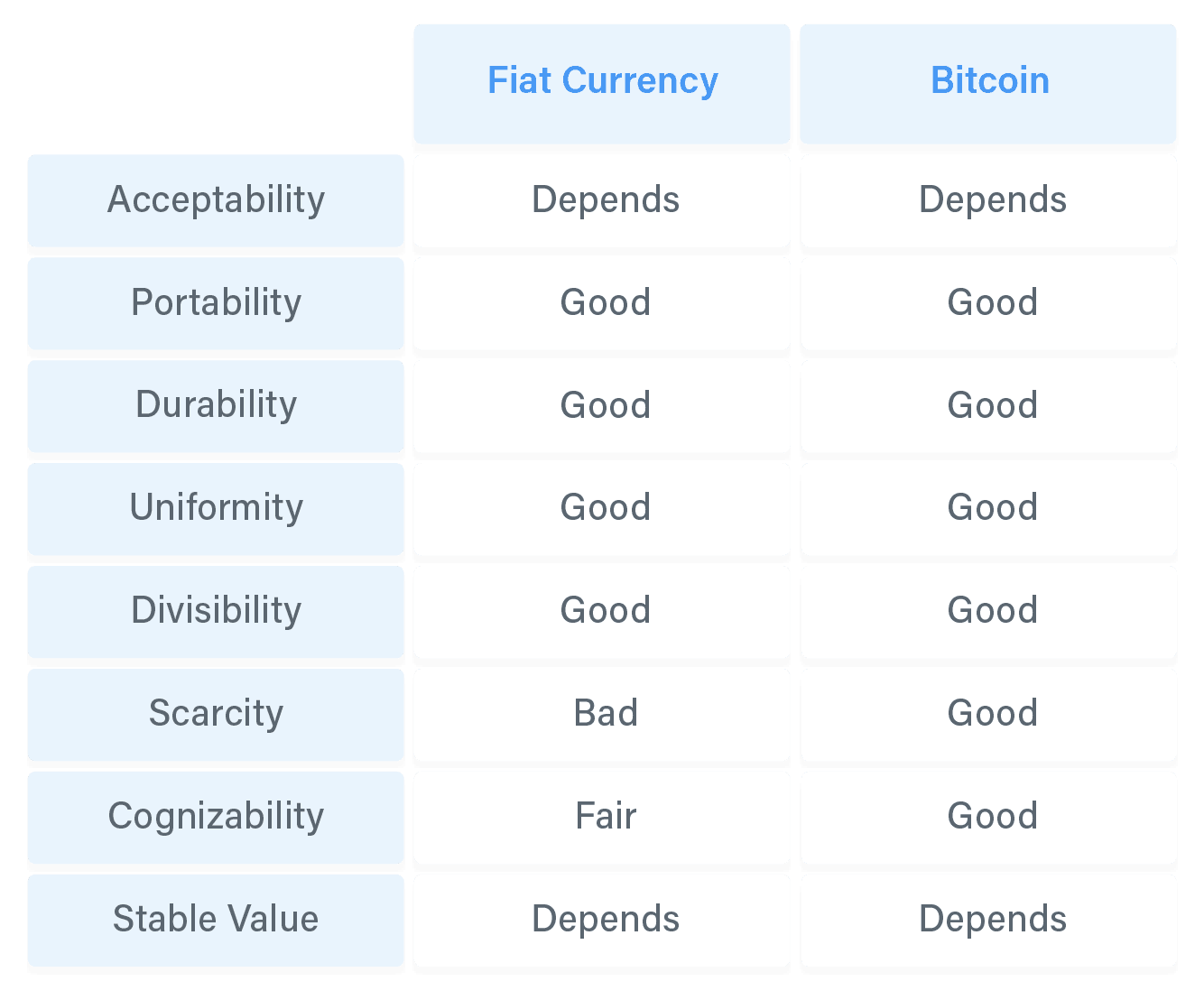

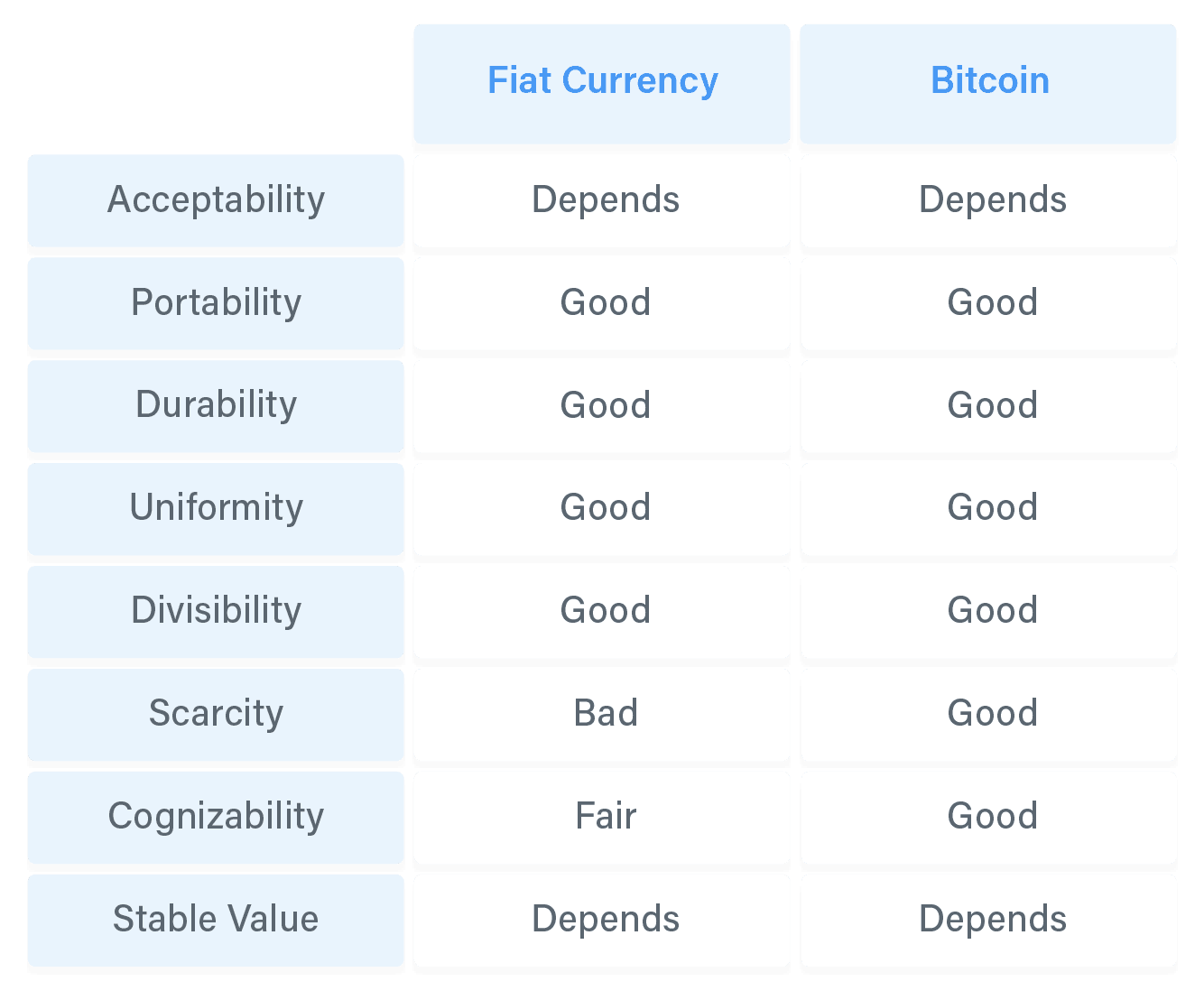

Using the criteria we used before:

We can see that bitcoin is a more ideal candidate to be a medium of trade than fiat currency. While fiat currency is more generally accepted and has a stable value, these are subjective measurements and can change through development over time.

However, we would like to name some key deficit that prohibits bitcoin to be used as money:

- Slow finality (needs at least 1 hour to confirm transactions)

- Limited throughput

- Requires sophisticated knowledge from its users (e.g. private key management)

These deficits do not exist for money of physical forms. Hence, for bitcoin, and cryptocurrencies in general, to be mass-adopted as money for daily transactions, we believe that solving the blockchain scalability problem is a prerequisite.

How to position bitcoin in the financial system

Bitcoin is also neither commodity money (since it has no intrinsic value), representative money (as it is not pegged to something with intrinsic value), nor fiat money (as it is not backed by the government). It is of its own kind, which we call decentralised money.

The value of bitcoin is solely determined by the market equilibrium between the people who trade it. This is in line with the subjective theory of value which states that:

“Value of a good is not determined by any inherent property of the good, nor by the amount of labor necessary to produce the good, but instead value is determined by the importance an acting individual places on a good for the achievement of his desired ends.”

Bitcoin is “hard money”. As Ammous has pointed out in his book “The Bitcoin Standard”: For every other money, as its value rises, those who can produce it will start producing more of it.21 The decentralised nature of bitcoin ensures that no single entity has the power to create more bitcoins out of thin air. Hence, another important characteristic of decentralised money is that its scarcity is guaranteed by decentralisation.

To conclude, bitcoin fulfils most qualities as ideal money. Its supply is also fixed in contrast to that of fiat currency. It may take longer for bitcoin to become a true medium of exchange, but the process for mankind to search for better money never stops, and we believe that bitcoin (and cryptocurrencies in general) will be a very strong candidate to position itself as the future of money.

References

1. Barter. (2020, January 21). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barter

2. History of money. (2020, January 24). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_money

3. Davies, R., & Davies, G. (n.d.). Chronology of Monetary History 9,000 – 1 BC. Retrieved from http://projects.exeter.ac.uk/RDavies/arian/amser/chrono1.html

4. Singh, J. (2015, August 18). Top 8 Qualities of an Ideal Money Material. Retrieved from http://www.economicsdiscussion.net/money/top-8-qualities-of-an-ideal-money-material/609

5. History of money. (2020, January 24). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_money

6. M. Kroll, review of G. Le Rider’s La naissance de la monnaie, Schweizerische Numismatische Rundschau 80 (2001), p. 526. D. Sear, Greek Coins and Their Values Vol. 2, Seaby, London, 1979, p. 317.

7. Ancient Greek coinage. (2019, December 16). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Greek_coinage

8. Banknote. (2020, January 29). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Banknote

9. Commodity money. (2020, January 28). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Commodity_money

10. Representative money. (2019, June 20). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Representative_money

11. Fiat money. (2019, December 25). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fiat_money

12. Gold standard. (2020, January 4). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gold_standard

13. Feenstra, R. C., & Taylor, A. M. (2017). International macroeconomics. New York: Worth Publishers: Macmillan Learning.

14. Impossible trinity. (2020, January 30). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Impossible_trinity

15. Fiat money. (2019, December 25). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fiat_money

16. Subprime mortgage crisis. (2020, January 25). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Subprime_mortgage_crisis

17. Quantitative easing. (2020, January 16). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quantitative_easing

18. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/bst_recenttrends.htm

19. John Rentoul @JohnRentoul. (2016, July 12). This is what Theresa May said about the kind of Prime Minister she’ll be – and what she really meant. Retrieved from https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/theresa-may-what-kind-of-prime-minister-policies-what-she-really-meant-a7130911.html

20. Nakamoto, S. (2009, February 11). Bitcoin open source implementation of P2P currency. Retrieved from http://p2pfoundation.ning.com/forum/topics/bitcoin-open-source

21. Ammous, S. (2018). The Bitcoin Standard: The Decentralized Alternative to Central Banking. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc.